With only 3 ingredients you can make a tasty gel within minutes. The gel is very fragile and easily “looses” liquid, in this case whey, which is seen as a clear drop under the spoon. This loss of liquid from a gel is known as syneresis.

Some weeks ago, while doing research for Texture on gel formation in foods where no “external” hydrocolloid is added, I came across ginger milk curd (in Chinese: 姜汁炖奶/薑汁撞奶). With only three ingredients – milk, ginger and sugar – it immediately caught my attention. I found a recipe and my first attempt was successful. I was amazed! With three seemingly simple ingredients I was able to form a tender, fragile gel within minutes. I loved the strong ginger taste with a touch of sweetness. After my first success I had several failed attempts, so I looked up some more recipes. What puzzled me was that, as I dug up more recipes, the different instructions were specific, but also contradictive. I couldn’t let go at this point, so I continued reading – also scientific papers. Now that I have a fairly good understanding of the science behind ginger milk curd it is clear that the many recipes I had found were full of kitchen myths.

Here are some examples (both right and wrong!) to illustrate the spectrum of advice given:

- Ginger: use old ginger, the gelling comes from the white sediment in ginger juice, by some referred to as “starch”, peel ginger with a spoon as the “starch” is right below the skin

- Milk: let the milk boil; do not let the milk boil; heat milk to anywhere between 60 and 95 °C; cool milk/cool milk a little/do not cool milk; pour back and forth between two containers 10 times; use full cream milk; do not use UHT milk; do not use pasteurized; pasteurized milk is OK; do not used homogenized milk; use “micro filtered” (?); etc.; use milk with higher protein content (or try soy milk)

- Recommended milk:ginger ratio varies from 8:1 to 25:1 (i.e. for 250 mL of milk use anywhere from to 10-30 mL of ginger juice)

- Pour milk in one go into ginger juice (hence the chinese name “ginger hits milk”,) , do not stir. If milk is poured too slowly or from low height the results is a very runny gel.

- For a firmer gel omit sugar

- Add a few drops of vinegar to help the milk curdle

- … and so on

It’s fascinating how a recipe calling for only 3 ingredients can lead to so many awkward instructions. No wonder then that I found reports from people who only succeed on 50% of their attempts, have succeeded on their 9th attempt or have given up and added egg whites (claiming the preparation requires “a lot of skills and a pinch of luck”). Kitchen myths arise when people randomly fail and succeed with a recipe. Depending on the outcome they try to attribute the result to something they did different from last time. There is a chance that this was a relevant change, but more often than not it has nothing to do with the outcome. With the wrong conclusion drawn the kitchen myth is a reality.

If you read on you’ll find a recipe for a fool-proof ginger milk curd as well as a scientific explanation of how the milk can set so rapidly upon mixing with the ginger juice.

Microplane the ginger, squeeze out the juice and pour the milk from a height so that it is instantly mixed with the ginger juice. Leave to set.

Based on what I’ve read so far, this is my “best bet” for a ginger milk curd that will not fail. The most important piece of equipment is a digital kitchen thermometer. If you don’t have one – get one!

Fool proof ginger milk curd

250 mL skimmed milk

18 g fresh *) ginger juice **)

20 g sugarCombine milk and sugar in a pan and heat carefully to 65 °C. Peel and microplane ginger, and squeeze out the juice. Place juice in a bowl and pour milk into the ginger juice from a height to allow sufficient mixing. Do NOT stir as this will interfere with the gel formation. Leave to set at room temperature. After 5-10 min a gel has formed. The curd may be served immediately or kept in the fridge.

In this recipe I used a milk:ginger juice ratio of 14:1. You can certainly use more ginger juice, but the taste of ginger may then become too powerful. You can also reduce the amount of ginger juice, but this I havent’ tested yet.

*) See comment below regarding the stability of the enzymes. Ginger juice should not be made in advance due to a short half-life in room temperature.

**) 18 g ginger juice = ca. 31 g peeled ginger = ca. 43 g raw ginger.

With only 3 ingredients you can make a tasty gel within minutes that can carry the weight of a spoon! Notice how elastic the gel is. After the picture was taken the spoon could be removed, leaving the gel intact.

Mechanism of gelling

Ginger milk curd belongs to a large group of foods where enzymes are used to curdle milk (including cheese of course). Traditionally one would use rennet to prepare such a curd. Rennet is found in the stomach of young mammals and is essential as they digest their mothers’ milk. The active enzyme in rennet is chymosin, also known as rennin. This is a proteolytic enzyme, also known as a protease. These enzymes are capable of breaking proteins into smaller fragments.

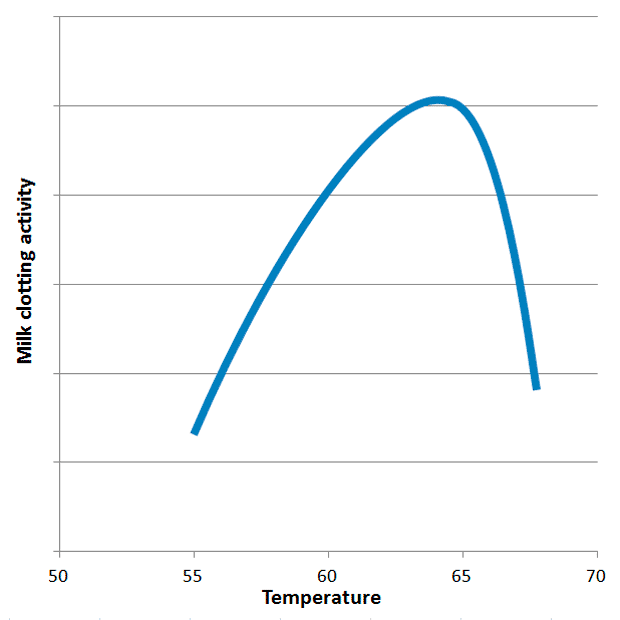

Ginger enters the scene because ginger also contains proteolytic enzymes. The ginger proteases (GP, sometimes called zingipain, EC 3.4.22.67) are very sensitive to temperature. At temperature above 70 °C they are rapidly denatured (=irreversibly destroyed). This explains why so many people fail when trying to make ginger milk curd. The milk clotting activity (MCA) of GP peaks around 63 °C and falls off rapidly above 65 °C and below 60 °C (see figure below). This means one is left with a relatively narrow temperature window of 60-65 °C. GP does show proteolytic activity (PA) outside this window, but this PA is more of a non-specific kind. MCA on the other hand is related to a specific hydrolysis of κ-casein (more on casein in a second, the greek letter κ is pronounced “kappa”). By now you may wonder if it’s possible to make cheese with ginger – and the answer is yes. Scientists have studied several plant extracts and found that ginger, kiwi and melon all contain proteases with a relatively high MCA/PA ratio (albeit not as high as that of chymosin found in rennet). The temperatures for maximum milk clotting activity of kiwi and melon proteases are 40 °C and 70 °C respectively.

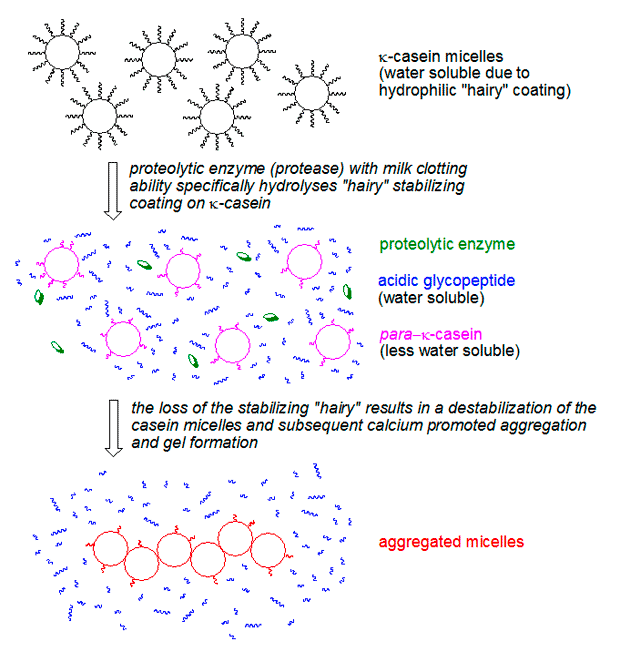

Enzymes are catalysts, the tireless workers responsible for building the gel. But it is casein, a group of proteins found in milk, which is the actual building block of the gel. The casein proteins group together to form large balls known as micelles which are held together by calcium ions. The outside of the micelles is covered with κ-casein which is composed of a water soluble part (an acidic glycopeptide) and another part which is much less soluble in water (para-κ-casein). The water soluble part migrates to the surface and leaves the micelles covered by a “hairy” layer. This layer both keeps the micelles dissolved in water, and prevents the micelles from coming so close to one another that they would coalesce and aggregate.

It is thanks to this “hairy” layer that milk is stable (i.e. does not spontaneously form a gel), and all is well until we add the above mentioned proteases to milk. What chymosin, GP and other proteases do is to cleave of the water soluble part of κ-casein, leaving para-κ-casein behind. Suddenly the micelles can collide, and the calcium present in milk aids in the formation of aggregates. These aggregates of “shaved” micelles make up the actual gel. It all happens within a couple of minutes. The resulting gel is very fragile and easily looses water, a process known as syneresis (see the top picture in the post).

I mentioned above the very narrow temperature window for GP, but one remaining question was whether heating milk to a higher temperature (before cooling to the same temperature window) would be beneficial. It turns out that if milk is heated above 65 °C, the strenght of the resulting gel is reduced. The reason is that the heat causes compounds in the milk (lactoglobulins) to precipitate onto the κ-casein. This interferes with the gel formation. The same is true for milk fat, so skimmed milk is the choice for a stronger gel. Since calcium plays a role in the aggregation of the “shaved” micelles, a higher calcium concentration will also result in a stronger gel.

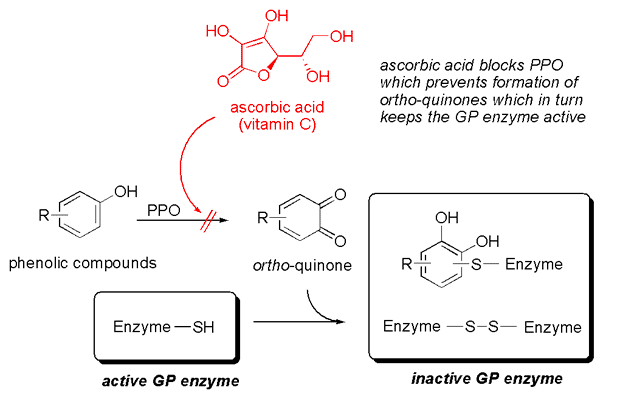

The ginger juice also deserves a couple of extra words. In freshly squeezed ginger juice the GP has a half-life of 20 min at 30 °C, so in a warm kitchen, half of your enzyme activity is lost 20 min after you have grated and squeezed your ginger. If you leave it another 20 min you’re only left with 25% of the original activity. This means that the ginger juice can’t be prepared in advance or stored unless you use a little trick. The reason for the instability is that ginger also contains another enzyme, polyphenol oxidase (or PPO for short) – the same enzyme that is responsible for the browning of apples (an example of enzymatic browning, as opposed to the Maillard reaction which is an example of non-enzymatic browning). Once the ginger has been grated, PPO attacks phenolic groups yielding ortho-quinones. These in turn can react with the GP enzymes to inactivate them. A well-known trick to prevent the browning of apples is to use ascorbic acid (more commonly known as vitamin C). Ascorbic acid blocks the action of PPO, which in turn prevents the inactivation of the GP enzymes. And the same trick also works for ginger juice. If you need to make ginger juice in advance, just add a pinch of vitamin C (0.2% to be precise).

Ideas for further experimentation

Even though I’ve arrived at a recipe which seems to work fine, there are several claims that remain to be tested – feel free to join in on the experimentation (or share it as an idea for a school science project)!

- old vs. young ginger: I believe the ginger I can buy in Norway is not particularly young, so this is not something I’ve actually tested, but my guess is that this is far less important than temperature

- milk:ginger ratio – what is the minimum amount of ginger juice required to make the gel set?

- pour low vs. high: I believe the point of the “high pour” is to avoid any extra mixing/disturbing of the gel

- mix within the first couple of seconds: not necessary if one does a “high pour”, but mixing in the first couple of seconds should be OK, however it’s not been tested yet

- mix cold, then heat: not tested, but should work

- lemon juice contains vitamin C, so perhaps some drops of lemon juice could help stabilize the ginger juice?

- firmer gel with less sugar: not tested, but tastewise this is not relevant – and I did get a nice gel with sugar, so it’s hard to motivate this

- addition of vinegar: not tested

- add ginger juice to when the milk hits 60-65 °C: this works, but is only practical if you want to make the gel in the pan used to heat the milk, as you will probably (i.e. I have not actually tested this) not have time to pour the combined milk and ginger into a second dish; perhaps this would be relevant if making ginger curd in a microwave?

References

Mazorra-Manzano, M. A.; Perea-Gutiérrez, T. C.; Lugo-Sánchez, M. E.; Ramirez-Suarez, J. C.; Torres-Llanez, M.; González-Córdova, A. F.; Vallejo-Cordoba, B. “Comparison of the milk-clotting properties of three plant extracts” Food Chem. 2013, 141, 1902-1907. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.05.042

Su, H.-P.; Huang, M.-J.; Wang, H.-T. “Characterization of ginger proteases and their potential as a rennin replacement” J. Sci. Food Agric. 2009, 89, 1178-1185. DOI: 10.1002/jsfa.3572 [free pdf here]

Further reading

Chen, Y.-Y. “Factors Affecting Protease Activity of Ginger and Its Application in Milk Clotting Products”, 2004, Thesis (Language: Chinese).

I commented a little while ago about this and WHOA. This is incredible stuff, thank you for your research (I love this dessert, if you can’t tell already)!!

I found a while ago about the properties of ginger when trying to make ginger ice cream. I put the ground ginger into the warm milk, and I got a few spoonfuls of clotted milk… The ice cream was not bad even without the milk proteins (I used egg yolks as a thickener, so I guess it didn’t matter so much). After that, I remembered reading Hervé This about this, and confirmed what happened.

Matthieu: Do you remember where Hervé This writes about this?

Thanks!! I’d failed at this once, and attributed it to the recipe insisting on young ginger, but realize now it was probably the (non-specified) heated milk temperature that caused the failure.

The research is great!! thanks a lot.

In Buenos Aires is difficult to find pasteurized milk, so to my first attemps I`ve tryed ultra pasteurized milk and it didnt work. I went to Uruguay and with “leche fresca” pasteurized milk …. and works perfectly!!

Mariana: Perhaps not so surprising considering that UHT milk is heated to >135 °C for 1-2 seconds.

it is incredible that it took you to understand and explain the science behind the ginger milk curd. it is just frustrating in reading all the chinese / non-chinese recipe and the kitchen myth that they propagate – and not able to understand why I am not getting consistent results.

Do you think trying to add some more calcium ions to the milk via calcium chloride (from the spherification days) would make a stronger gel? I will do that experiment soon 🙂

pigflyin: Yes – adding calcium chloride (or preferably a calcium salt that is not bitter, such as calcium gluconate) will yield a stronger gel. I’m not quite sure though whether one can dissolve calcium salts “just like that” in milk, or if you need to take special precautions to avoid precipitation. I guess you simply have to try…

Martin: no sorry, I couldn’t find it anymore. Hervé This however indicates in De la science aux fourneaux (Belin – Pour la science, 2007) that artichoke flowers (and other plants in the thistle family) contain an enzyme that can replace rennet in making cheese (a fact that was empirically known a few hundred years back already; I just found this article on the french wikipedia http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caillebotte_%28fromage%29 regarding this type of preparation). Regarding the ginger, I might have found the information on the web (after my unfortunate experiment) on a forum about vegan food… I really can’t remember 🙁

Regarding calcium salts, This also advocates the use of calcium citrate (made of egg shell dissolved in lemon juice) instead of the (toxic) copper ions from the copper pan to strengthen the pectin gel in marmelade and jams. Since the ginger is going to curdle the milk anyway, I would guess that the citric acid may not have any adverse effect (but then again, I have not tried 🙂 A footnote on the Caillebotte article quoted just above indicates that the use of an acid to provoke the coagulation of the milk proteins will make the coagulation too fast and causes the proteins to floculate at pH 4.6 (how much this pH value is relevant, I don’t know).

Regarding UHT milk: I’ve read many times that proteins in UHT milk are quite much affected by the UHT process, possibly making them unable to curdle?

Just as a little follow-up note, I would like to mention that there are several Portuguese cheeses made with thistles, rather than rennet (now part of the Ark of Taste).

Afaik, historically and at least in Finland, maybe also in Scandinavia, they used yellow bedstraw (Galium verum) for making cheese. (It was called also “corpse hay” or something like that, for it was put into coffins to prevent smells.)

I have a very stupid question.

Kiwi (or melon?) curd do not sound so interesting taste-wise.

So what about pineapple?

The problem is that not being an expert it is difficult to find relevant literature.

What about refrigerating the ginger juice before mixing to decrease the enzyme activity?

The recipe works perfectly. I did not have skimmed milk but reduced fat milk (1.5% fat) in the fridge so I used that. I noticed a nice gelly ginger curd with a strong ginger flavor to it.

There was a lot of whey underneath the gel, at least 2 to 3 mm height on the bottom of the bowl. Is this the result of using reduced fat milk?

MF: Pineapple contains the protease bromelain, so yes – this can also be done with pineapple juice (fresh that is – not canned). Wikipedia claims the “optimum temperature for maximum cumulated activity over time is 35–45 °C”. A patent indicates the temperature range 26-31 °C for bromelain used for milk clotting.

Josefin: Refridgeration will help retain enzyme activity, but I’d recommend to use fresh ginger juice, or alternatively add a little vitamin C/ascorbic acid.

Ron: Great! Yes – the curd is very loose and will easily loose whey (as you can also see from the picture in the top of the blog post), even if you use skimmed milk.

Have you tested out adding vitamin C/ascorbic acid and if so, what is a little? I get the impression that acid can easily over-curd the milk?

Where can one buy ascorbic acid in Norway, or maybe just dissovle vitC tablets in water?

I deviated from the recipe in 2 places – don’t work at all. I was anticipating a weaker gel but it turned out to be completely watery still after it cools down.

* I used full cream milk instead since I don’t have skim on hand

* I didn’t peel my ginger before i grate them. (? don’t know if it matters?)

I have put a timer on to see how ‘old’ is the ginger juice when I pour the milk… i was about 8 minutes at 28C (yes, I am at southern hemisphere).

Questions aside, more basic trying to go.

I just tried today and it worked well. The surface was unevenly coloured white and yellow, as if oil (?) in the ginger juice floated above the water of the skimmed milk without mixing properly, but the texture and the taste were great.

I added a random pinch of ascorbic acid (in Finland at least, you can buy it powdered, in bags of 20g at the pharmacy) and I could notice no adverse effect.

Josefin: The paper by Su et al. referenced above mentions that the activity of the enzymes when stored at 5 °C for 4 days is reduced to 20% of the initial activity. I would guess that the activity drops the most initially. Regarding ascorbic acid the authors of the same paper 0.2%. For the 18 g of fresh ginger juice this would correspond to 0.036 g = 36 mg. A quick google search shows that many Vitamin C tables contain 500 mg of ascorbic acid, so if you scratch off a corner of a tablet that should be sufficient. On the other hand it wouldn’t hurt using a whole table. If you try – please report back.

pigflyin: Was the full cream milk UHT treated or just pasteurized (or to put it differencetly: was the milk stored at room temperature when you bought it or in a fridge)?

Matthieu: Interesting observation. Did you pour from a certain height?

Martin: Yes I poured from 15-20 cm high. All the milk curdled, so I guess the juice and the milk did mix well enough. But the color of the preparation was much more white than on your pictures, with the exception of the yellow spots on the surface. I’ll try again in a few days, I’ll take pictures.

My ginger juice was also a paler yellow than in Martin’s picture. Colour can differ.

The sieve I used was to coarse so I had a few ginger fibers in there which showed as yellow spots.

Maybe that is the same as you had?

I made a concocotion with whey protein, cocoa, banana, coconut milk and lacuma and I was surprised when it gelled after a few minutes. I had heated the coconut milk and let it cool very slightly. So I take it there must be an enzyme involved there too. Any idea where from?

pauline: That is very interesting! I’ve search, but cannot find that lacuma (Pouteria lucuma) contains proteolytic enzymes. And none of the ingredients you mention contain casein (the whey is what is left when you take the casein out). Based on this I think we can rule out a protease induced gelling of casein. But looking at the ingredients you mention I wonder if perhaps the alkaline cocoa powder could cause the whey protein to gel. I have seen reports of alkali induced gelling of whey. Does it gel if you leave the cocoa powder out?

Could it be pectins? I tried once to blend a whole tomato and leave it, and it gelled slightly shortly after. The source of this experiment is Hervé This (again), he mentionned in a radio show that pectins can bond without heating.

Matthieu: Yes – pectin could be involved. Does this fruit “Pouteria lucuma” contain pectin? You’ve probably seen my previous posts on tomato gels with the pectin that is there and gelling of ketchup with HRP?

Oh, so you know about gelling tomato, then 🙂 And I just noticed I had commented on the ketchup+horseradish article…

Success finally –

tried the 3th time and success with both skim and full cream milk – the main procedure that I change is that I read the post again – and I heat the milk up slowly (carefully) to 65C. Trying desperately to only change 1 variable at a time.

Next up, checking if older or younger makes a difference. the most prominent myth sounding kitchen wisdom amongst all my family and friends.

The gel strength & texture of skim milk is very different to full cream milk – skim milk gel have a clear separation of gel and whey.

I also found the full cream milk have a less pronounced ginger hotness even the sugar and ginger juice stays the same.

Hi:)

I really like your blog here. Interesting to me especially because I study food sciences. This ginger curd is genius. I really want to try make it, but before getting started and experimenting on my own I wondered if you have good tips or advice for what to use it with. Since it “looses” liquid so easily I have my doubts if it can be used in, let’s say, a cake or something similar. Maybe it’s better on the side with a fruit salad? What do you think?

Thank you again for a wonderful blog.

Math

pigflyin: Interesting with less syneresis when using whole milk. Look forward to hear how young vs. old ginger comes out!

Math: I prefer ginger milk curd on it’s own as a small dessert. The gel is so fragile – if you try to handle it, it will only be a mess.

Hi Martin,

Thanks very much for this post!

I am born a Cantonese and have lived there for 18 years, basically 姜撞奶 is something invented in my hometown province. 🙂 I love eating 姜撞奶 very much.

As I also write a food culture blog, last week I quote this interesting blog – I hope you don’t mind (I have given credentials of course) and I got a feedback from a reader. He says his family has been making 姜撞奶 for such a long time and he hasn’t failed once.

This is his suggestion:

1. He says temperature is crucial, but then the range as wide as 60-90 would do.

2. And you should not use skimmed milk, you should use buffalo milk if you can find any; if you don’t, you should use full-cream milk.

3. Adding milk powder is a trick, but that compromises the texture of the desert.

4. When cooling off, you can also consider putting the bowl inside warm water.

FYI. 🙂

Sylvie: Thanks for the comment! I agree that a higher temperature can work for several reasons: the milk will cool upon contact with the bowl. If poured from a height the air will also help cool the milk. Furthermore the temperature induced denaturation is not instantaneous, meaning that the enzymes can survive a higher temperature for a short time. But for a recipe this becomes very inaccurate as it assumes an unspecified cooling of the milk to occur. I agree that full fat milk may taste better (and that it works), but for a firmer gel skimmed milk seems to work better – at least that is what http://food.oregonstate.edu/learn/milk.html says.

Hey, just want to report that I’ve made it four times. First just like recipe, success. Second, I just eyeball it but fail because I think the ginger juice was too little, the milk didn’t curd. Third, I didn’t peel the ginger, just pound it to coarse paste then cooked it with the milk, sort of fail because there was curd but couldn’t strain it. Fourth, didn’t peel the ginger, pound to coarse paste and squeeze it, success. I’m using raw milk and is it possible to make the curd firmer? I hope I know better way in the squeezing part, or maybe I just don’t have the right tools. Anyway, awesome experiment though, thanks :D.

[…] The taste? Weird but nice. I googled about this strange mix and found out that indeed, this flavor is present in Guandogn province in China. It comes in the form of a dessert call ginger milk curd. The dessert is made of milk, ginger and sugar. For curious takes, the recipe can be found here. […]

Great success! Thank you very much for your instruction. We also succeeded with 13g of ginger juice.

A few more successes with less ginger juice as low as 6g as long as we carefully boiled the milk to about 65C. We used Great Value brand whole milk from Walmart. Tasted as good as the ones we enjoyed in Hong Kong. Thanks again for the fool-proof recipe!

I’m glad to hear that it worked! And thanks for measuring the amount of ginger juice you used. I’m curious: did you notice any difference in texture when using less ginger juice?

The good news is there is no visible and palatable differences so far. Traditional GMC tastes less “spicy” so we will experiment these:

1) Use whole, fresh cow’s milk directly from a farm.

2) Squeeze (with hand) the ginger juice right at the moment we are ready to add the milk to maximize the proteolytic reaction.

3) Refrigerate GMC at different lengths of time (eg., 10 mins, 15 mins,…, overnight) before serving.

We will share back. Going to a dairy farm today!

worked well as per recipe.

Very nice flavour and texture, pasteurised ss homogenised milk.

Thanks

Martin, we succeeded with using only 5 g of ginger juice and it tasted just right. Refrigerating the GMC overnight made it taste and feel like another dessert called Dou Fu Hua 豆腐花. All were very delicious! Thanks again for all your hard work and generosity in sharing the findings.

I tried it using your recipe and it set perfectly, but I found the ginger taste too overpowering, I will try using less ginger use next time. Thanks.

Martin:

Do you think this would work with the application of an immersion circulator? Mix the three ingredients together, seal and circulate to 65C? Then you might be able to hold it at that temperature to serve it hot?

Kristofer

That would work, but then it would gel in the bag. The gel is so fragile, so getting it out of the bag would ruin the texture. An alternative would be if you have serving size mason jars with rubber gaskets that could be submersed. Perhaps you could manage with less ginger if you could keep the optimum temperature for a longer time.

My experimental using condensed milk.

250 ml of condensed milk*

17g of fresh ginger juice**

20g of regular white sugar

I poured the milk to the pan, added sugar and started heating it on low/med (North west knob position for central european folks). It took about 7 minutes to reach 65C.

In the meantime I peeled and microplaned the ginger which I then pushed through a sieve to obtain ginger juice.

After the termometer alarm went off at 65C I removed the pan from the heat and pour it from about 30cm high to the cup containing ginger juice.

I set it all aside for 10 minutes and it thickened! Really lighty but enough to hold a spoon on top of it. However when a took a spoon to taste it, small amount of liquid appeared on the surface of the spoon.

Hello to all, what a great thread, it is all very informative–thank you. I am throwing one new, quick, general question: any idea of how to avoid, or delay, the syneresis without altering the texture of the curd?

Stefano: You could try with a little (start with something like 0.2-0.3%) xanthan, a hydrocolloid typically used to reduce syneresis in various food preparations (see “Texture” for a range of examples). Whisk it into the milk prior to heating it – and let me know if it works!

Personally, melon or kiwi versions sound amazing. could you simply substitute ginger juice for kiwi. or honeydew juice? I would give it a shot, but I don’t have proper ingredients.

As a food scientist with more than 25 years at the dairy industry, I’ve really deeply enjoyed this post!!! You’ve done a really great job. Congratulations, and please keep on doing it.

Thank you so much for your simple and precise recipe! Ginger milk curd/薑汁撞奶 has been one of my favourite desserts since childhood. Whenever I asked relatives how to make this dessert, they all brushed it off as being very finicky and easier to enjoy at a restaurant rather than to bother making it at home. But following your instructions, I have successfully made my own! While the result was a lighter custard than I expected (if familiar with Chinese desserts, this recipe yields a texture much closer to dou fu fa 豆腐花) I suspect this is because I’m used to eating ginger milk curd that has be double steamed which results in a much firmer and “older” texture.

What a fantastic blog post! This is what the web was all about before it became a commercial mess!

Very very cool! Love the simplicity of style in the explanation – without sacrificing precision! I can see you clearly love chemistry and cooking! I do too – but with out the ability to write nearly as well 🙂

I’ve always viewed cooking as a “complex” phenomenon – blends mathematics, physics, and chemistry to achieve something magical.

I absolutely love the MCA curves for ginger juice – takes this to a new level! I’m inspired to try this sometime soon!

Thanks for the great post!

Thank you for your kind feedback – I’m glad you liked the post. Have tried making ginger milk curd yourself? It has a really fascinating texture!

This was a great read! I had never heard of this & recently found a recipe on a cooking website. It worked the first time using “longlife” (i.e. heat-treated and refrigerated, not UHT) full fat milk (70 °C) and 12ml freshly prepared ginger juice for 200 ml of milk (plus two teaspoons of sugar). Curdling was almost instantaneous. I let it cool down and served it about 90 mins later.

I did notice a very faint bitter taste and was wondering about other people’s experiences. I know that other plant proteases (from pineapple or kiwi) will result in a quite bitter taste in combination with milk, but did not find anything regarding the ginger protease.

Thanks again for the great post!