Cloning popular brands of mineral water is now simpler then ever before with the updated version of the mineral water calculator!

When I blogged about DIY mineral water last year it was mainly a theoretical exercise since I didn’t have the required salts at hand. My experience was limited to adding some baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) to water before carbonation. Luckily Paul Hinrichs tested the calculator! In the meantime I have purchased the required salts and with several kilograms in total I’m probably well stocked for the next decade! Based on the output from the calculator, I mixed the salts required to clone San Pellegrino, added water and carbonated the mixture. And the good news is that it works! The water tastes great and I’ve been enjoying cloned mineral waters every day now for the last couple of weeks.

Some changes have been made to the mineral water calculator (Updated! – scroll down for download options) since I last posted:

- a simpler worksheet more suitable for printing has been added

- more mineral waters have been added to the database, covering TDS (total dissolved solids) levels all the way up to more than 4000 mg/L

- potassium bicarbonate, magnesium chloride and calcium nitrate are made optional and can be left out if desired (it’s still a little unclear to me to what extent these can be detected at the typical levels found in mineral waters)

- one can now chose between using either hydroxides or carbonates of calcium and magnesium, depending on availability (it should be noted however that some waters high in bicarbonate may require the use of the hydroxides – not quite sure about this though)

A spoon full of mineral salts is required for the preparation of 1 liter of San Pellegrino mineral water.

Instructions for how to prepare the mixture of salts

Start by chosing the mineral water you want to clone from the drop down list. My advice would be not to start with the waters having very high levels of total dissolved solids (TDS) (except Kessel and Vichy Saint-Yorre since sodium bicarbonate dissolves easily). Aim for a TDS in the range 200-1500 mg/L (the list of all mineral waters in the rightmost worksheet is viewable and sortable). At the lower end you may not detect much mineral taste at all. At the higher end the mineral taste becomes quite pronounced. You can click the check boxes to include/exclude some salts. If known enter the composition of your tap water (your local water company should be able to give you these figures). I suggest that you weigh out the salts for 10 or even 100 liters, otherwise the amounts of salts will be in the low milligram or microgram range, requiring expensive lab scales. Mix the salts well. It may be god to start by mixing the salts present in the lowest concentrations first to ensure a homogeneous mixture.

How to make a cloned mineral water

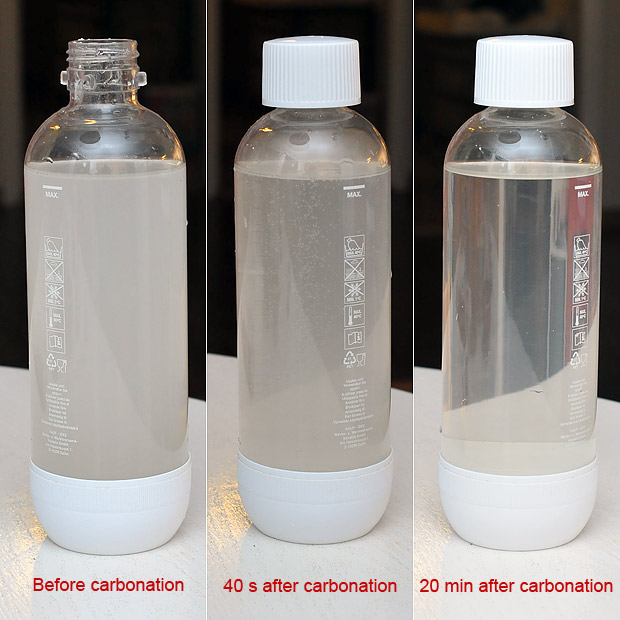

Weigh out the approximate amount of salt (prepared as described above) needed for the amount of water that your carbonation vessel holds. At this point it doesn’t need to be very accurate, so if you have weighed it once you can simply need to remember which spoon you used and the size of the heap. Note that the different mineral salts vary greatly in density, so you should calibrate the heap used for each mineral salt mixture. Add the salt to the carbonation vessel and fill it up to the mark with water. The water will now turn opaque and whitish as the salts are suspended in the water (see picture above). Carbonate carefully and, depending on whether the water is high in carbonation and/or bicarbonate, try to hold the carbonation pressure for a couple of seconds extra before letting the pressure out. This allows a little more carbon dioxide to dissolve. Screw on the cap immediately to prevent the carbon dioxide from escaping. In some cases it may be necessary to repeat the carbonation step after some hours. Once the salts have dissolved (i.e. the water becomes clear) you can enjoy your very own home-made mineral water!

Several of the mineral salts have are not soluble in tap water, hence the opaque look to the left. After carbonation however they dissolve rapidly.

So far I’ve made up the salt mixtures for San Pellegrino (total dissolved solids, TDS: 1109 mg/L) and Gerolsteiner (TDS: 2488 mg/L). The first works like a charm, even when all salts are added simultaneously. This is possibly due to the high amount of sulfates which seem to dissolve more easily. Gerolsteiner is more tricky, partly due to the high TDS and the low amount of sulfate. I made it using carbonates instead of hydroxides, hoping that this would require addition of less carbon dioxide to neutralize the base. But after two days and 2-3 extra additions of carbon dioxide the salts had still not dissolved completely and this puzzles me. I certainly need to repeat this experiment. Darcy O’Neil states in Fix the pumps that the order of addition does matter. I’m not quite sure if that really is the case as most of the salts have a very low water solubility to start with, and the carbonic acid is the reason they dissolve. But maybe there is something I’m overlooking here? It could be that Gerolsteiner is easier to do with hydroxides, but Paul Hinrichs also had some trouble getting all the salts to dissolve for Gerolsteiner.

Some of the salts may be tricky to obtain, but the synonyms below may be of some help:

- CaSO4·0.5H2O = Plaster of Paris

- MgSO4·7H2O = Epsom salt

- CaCO3 = Chalk

- NaHCO3 = Baking soda

- NaCl = Table salt

- Mg(OH)2 = Milk of magnesia

- Ca(OH)2 = Slaked lime, pickling lime, CAL

Before you rush to buy these salts I should probably add some words of warning: make sure that the source you find is suitable for consumption! Some technical qualities of mineral salts may not be intended for food use, for instance due to the presence of heavy metals or other contaminants. Note that some of the salts are available with varying amounts of crystal water. If you use other salts than those specified (i.e. anhydrous salts or salts with more crystal water) the molecular weights in the spreadsheet need to be adjusted for this. I guess that if you are familiar with the concept of crystal water, you’ll easily figure out the correct molecular weight and how to update the calculator according to the specific salts you chose to use.

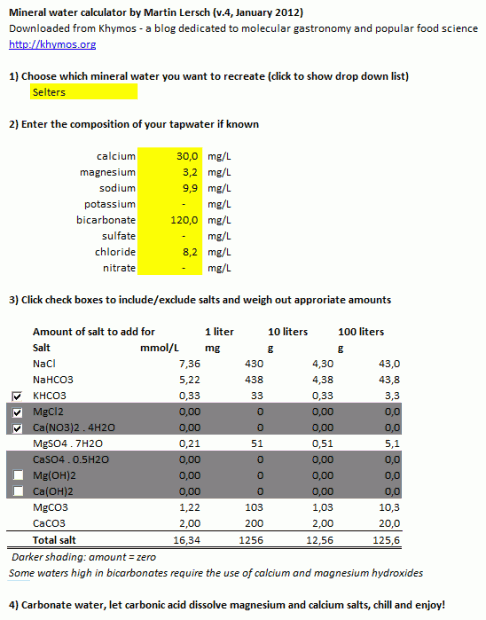

Screen shot of the simple version, best suited for printing (see below for download options):

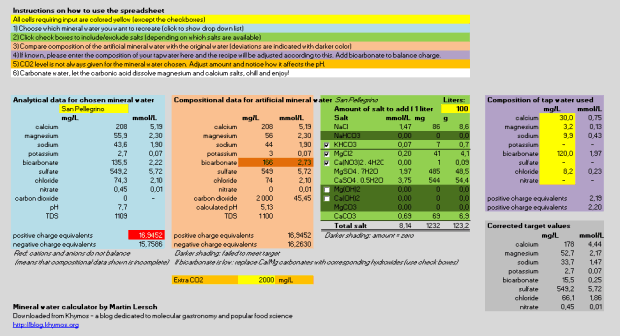

Screen shot of the complete version (see below for download options):

Calculator download options

Version 6 (latest update, January 2015 – some extra waters added)

Excel: mineral_water_calculator_v6.xlsx

Version 5

Excel: mineral_water_calculator_v5.xlsx

Open office: mineral_water_calculator_v5.ods

Version 4 (the version originally provided with this blog post – contains errors)

mineral_water_calculator_v4.xlsx

Mineral waters included

Mineral waters included in the database that comes with the calculator: Acqua Panna, Antipodes, Apollinaris, Aquarel Birken, Artificial mineral water, Badoit, Borsec, Burton (beer brewing), Calistoga, Carola Rouge, Contrex, Dorna, Evian, Farris, Fiuggi, Gerolsteiner, Harghita, Hassia Sprudel, Henniez, Kessel, London (beer brewing), Mountain Valley Spring, Munich (beer brewing), Neuselters, Perrier, Pilsen (beer brewing), PurPur (coffee brewing), Rosbacher Klassich, Saint-Yorre, Salvus, San Benedetto, San Narciso, San Pellegrino, SCAA target (for coffee brewing), Selters, Tea brewing (max), Tea brewing (min), Tesanjski Dijamant, Topo chico, Ty Nant, Vittel, Volvic, Voss, Waiwera. And you can easily add data for other mineral waters. The websites mineralwaters.org, finewaters.com and Mineral water atlas of the world have data for several hundred waters available. And if you have a bottle of your favourite mineral water at hand you only need to check the label to find the required input for the calculator.

Thank you for the fantastic information! Could you please help explain how you converted an annual water analysis report from general minerals into your recipe? For example, Orezza water report lists “Calcium” as 185 mg/l. How do you determine which calcium to use , and how much of each? Calcium nitrate, Calcium Sulfate, Calcium Hydroxide, Calcium Carbonate, Calcium chloride … Is there a spreadsheet available to help determine this?

Thank you for the fantastic information! Could you please help explain how you converted an annual water analysis report from general minerals into your recipe? For example, Orezza water report lists “Calcium” as 185 mg/l. How do you determine which calcium to use, and how much of each? Calcium nitrate, Calcium Sulfate, Calcium Hydroxide, Calcium Carbonate, Calcium chloride … Is there a spreadsheet available to help determine this?

@Joel: A water report would normally also include the anions (i.e. the negatively charged ions), not only the cations (= positively charged ions) such as calcium. If I were you I would reach out to your water supplier and ask for the full analysis report.

Thank you for your reply. I am not looking at my own water analysis. I am interested in “cloning” other interesting waters that are not included in your spreadsheet, such as Orezza, as I mentioned. But, I just noticed that I can enter the units into your spreadsheet on the ‘lookup’ tab, and it will calculate the quantities automatically. I had assumed that would have to figure that out by myself!

Awesome spreadsheet and so much fun! I also brew beer, so I have kegs and taps free for waters. It’s a great addition to the lineup!

@Joen: Sorry for misunderstanding – great you figured it out! I found the following composition for Orezza water.

Typical Analysis (mg/L)

Calcium 185

Magnesium 16.5

Sodium 6.9

Potassium 1.55

Bicarbonate 710

Chloride 10

Sulfate 14

(Fluoride 0.17 => will not influence taste, so skip this)

If you enter this the spreadsheet should help you figure out which salts to use!

This is awesome! I am a bit confused. It says amount of salt to add for 1 liter, next to that in the yellow box it asks you to input total liters. Is the total amount of salts given per liter or for the entire amount of water?

@Nate: It does both! It calculates the amount for 1 L as well as the other amount (e.g. 100 L if you make a large batch). Note that the unit for the 1 L column is “mg” whereas it is “g” for the column next to it.

Hi Martin, thanks for all this effort. Can you help with an odd issue? I used your excel file to make Acqua Panna still water. However, upon drinking the water, I experience a sensation in my mouth almost like ‘numbness’ or ‘discomfort’. Any idea what would cause that? I drink Acqua Panna still water from the factory normally.

@Michael: I’m not sure what could cause this. Are you sure you got the salts and the concentrations right? One liter of Aqua Panna water requires well below 1 g of salt – in fact only 0,16 mg if using distilled water. This is literally only a small pinch. Could you by accident have used a much higher concentration?

HI Martin, my scale is not sensitive enough to make one liter. What I did instead was, add the correct amounts of salts to create 10 liters of water to 1 liter bottle of water (as a concentrate). Then I took 75ml of the concentrate and added it to a 750ml glass bottle of water. I have old Acqua Panna 750ml glass bottles that I am using for this experiment. I hope my math was correct.

Hey thanks for you effort putting this info together. Super cool to mess around with.

I had one question about the calculator I can’t quite work out. For the green table that tells you the amount of minerals to add given your starting water composition, what does the dark green shading mean?

The legend says dark green shading means zero but then i do have dark green shaded cells that have a value in them that isn’t zero.

It might just be shaded because the cell for g is zero?

an example: MgCO3 is shaded dark green

————————————————

| Salt | mmol/L | mg |. g

| MgCO3. | 0.03 | 3 |. 0.0

Thank you for your work. I begin to experiment with your calculator. Questions: 1- what are the salts that need carbonation to dissolve?

2- If these salts are not present in the recipe, would it be better to make a large amount of pre-mixed powder or a pre-disolved concentrated?

Thanks again

For those interested in the data flow and defined names of the calculator:

Analytical data for chosen mineral water

minus

Composition of tap water used (defined name example: Ca_p)

to

Corrected target values (defined name example: Ca_t)

to

Amount of salt to add for (defined name example: Calcium_carbonate)

to

Compositional data for artificial mineral water (defined name example: calcium)

As I understand it, the carbonate and hydroxide versions require carbon dioxide to dissolve.

If possible, it would be interesting to have the option to exclude these versions of salts in order to be able to use the calculator to create non-sparkling waters.

Thanks for a job well done!

Someone in the comments mentionned to adjust the resulted value when using gypsum (CaSO4.2H2O) over plaster of Paris (CaSO4.0.5H2O: multiple amount by 1,186

Do we have to adjust the following?

To use MgCl.6H2O instead of MgCl2 multiple amount by 2,135

To use Mg(HCO3)2 instead of MgCO3 multiple amount by 1,736

To use Ca(HCO3)2 instead of CaCO3 multiple amount by 1,620

Wouldn’t it make a lot of sense to start from distilled water rather than tap water?

For the purists out there, perhaps even distilling your own water after filtering it with a charcoal filter (Brita, Berkey, etc.)?

Or perhaps you can suggest other ways of getting as close to pure H20 before adding the minerals, etc.?

It seems starting with as pure a water base before adding the minerals makes sense, am i missing something?

Forgot to ask: where does one purchase the minerals to add to the water?

Do you recommend any certified sources that are not contaminated, etc.?

Thanks!

By the way, your captcha expires way to fast, i’ve had to reload the page several time and re-paste my comment!

@northislander: You can start with distilled water if you like. Simply adjust the composition of your starting water accordingly. The down side is that distilled water typically costs money. Buying salts: You’ll have to look around. Brewing stores, drug stores, etc. Try to get food grade salts.

@TP: If you prefer a non-sparkling water, but still want the salts I’d recommend to carbonate the water to get salts dissolved, and then leave it uncapped to let any excess CO2 out.

Great Calculator!

Has been very helpful since I make a lot of mineral water. I added a lot of recipes to mine and also a new column for converting Plaster Of Paris to Gypsum since thats easier to get for me.

Right now I have a keg of Gerolsteiner!

Seems to have worked perfectly using carbonates. I mixed the salts in the blender in two steps with 1.5l of water each. (NaHCO3 + KHCO3 and MGSO4 + MgCO3 + CaCO3) Then added those to the rest of the water to make 9l (2.5gal keg).

Carbonated at 70psi at 5 degrees C.

After a couple hours of shaking it was still cloudy. One day later I imagined to see some cloudiness and the taste was slightly chalky. Now it’s been 3 days on the CO2 and it’s clear. Compared it to a store bought bottle of Gerolsteiner and it’s really really close!

I measured everything on a 0.1g coffee scale so the subtle difference in taste might be due to me adding too much of something and 9l isn’t that much.

@Sven: Thanks for sharing your observation! I absolutely makes sense that time is key to get rid of the cloudiness. Keep in mind that minute taste differences may be caused by chemicals present in the base water you are using. Chlorine from water treatment is the first that springs to mind.

@Sven or @Martin: If the recipe calls for CaSO4 . 0.5H20 but I have CaSO4 . 2H20, how do you do the conversion? Thanks!

Look at my post of FEBRUARY 14, 2024 / 3:36 PM and

Matt post at JUNE 8, 2022 / 6:36 PM

Your answer is there

Hey friend, I’m trying to figure this same thing myself but have no chemistry knowledge at all.

Would you be willing to share a link to the CaSO4 . 0.5H20 or the CaSO4 . 2H20 that you purchased? It’s definitely been the most difficult to confirm I’m getting a food grade one.

I referenced your post that talked about multiples of 1,186.

Would this mean that to make San Pellegrino which calls for 5g/10L of CaSO4 . 0.5H2O, I would multiple 5g by one point one eight six? I’m assuming you’re from a country that uses commas instead of the decimal points used in the USA, as I don’t think I need to multiply the amount by a thousand.

In this case, I would use 5.93g instead of 5g correct?

Thanks for your help!

Hi Martin, thanks for this genius article i hope it leads to better things and inspires us to do something better. Id like to try it with local water here but with distilled instead water to take it a step further hopefully. I cannot find one ingredient and its Ca(NO3)2 . 4H2O. Is there another name for this? Thanks again

Pure ingredients gave me the following molecular structure for their magnesium carbonate: 4MgCO3.Mg(OH)2.xH2O

As Google can’t give me the weight of this molecule and I don’t have the knowledge to calculate it, I would appreciate if someone can help me. I would like to adjust the calculator. Thanks!

It depends on the x. If you assume x=2 the sum formula is Mg5C4O16H6 and the molecular weight 431.

Hi Martin

Thank you for your informative website. I would like to make some mineral water – but I am confused about acid and alkaline potential. I would like a water high in bicarbonates – as high as possible but not acidic because I have read the acidic load on the body over time erodes bone (especially with the western diet). I have osteoporosis at 49 years old and have read now many medical research studies showing bicarbonates seem to be the thing that make the difference to slow down bone loss but when I try to find a mineral water that exists that is 7 or above in pH I can’t find one. I have looked at Ferarrelle https://www.ferrarelle.it/assets/pdf/2019BWR_FerrarelleNMW_engl.pdf (page 13) which is high in bicarbonates but pH 6.2.

Also Kryniczanka from Poland which to me is the most interesting. It is the highest level of bicarbontes and is high in calcium and magnesium while not having too much sulphur or sodium https://kryniczanka.pl/wybierz-wode/kryniczanka/

However again this is pH 6.1 for Kryniczanka.

Why are all the high bicarbonate waters I find acidic and most usually, fizzy?

Is it possible to find a mineral water that is not fizzy (I’d prefer flat if possible!) that is high in calcium, magnesium and bicarbonates but not high in sodium, chlorine or sulphates and which is pH 7+?

Or is this just chemically impossible?

Does the acidic pH change once inside the body i wonder, due to all the dissolved bicarbonates? Why are these waters not more alkaline having so many metallic salts dissolved in them? Sorry for my basic chemistry but I remember the water turning purple with a pH test, most of the time, in class after putting metal in water like potassium.

Some studies in case it is of interest regarding mineral water and bone health:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0531513106005899

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022316622095669#bib9

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002916523071095

If it’s not possible, would you be able to help me make the Kryniczanka at home with the recipe?

Thank you again for your website. It’s given me some hope!

Your body alkalinity is not really dependent on the acidity/alkality of the liquids you consume. Think about it this way – you can have distilled water, add a few minerals that will make it extremely acidic or alkaline, but once you drink it, those few minerals will make no difference to your body’s acidity or alkalinity, because there’s so few of them. Likewise you can get “alkaline water filters” that add titanium and other toxic metals to make the water alkaline. Is this good for you?

Instead you should be focused on consuming the alkaline minerals, zinc, calcium etc. With regards to this aspect, focus on mineralisation and nutrition, not on the acidity or alkalinity of the specific liquids you’re consuming.

Where acidity/alkalinity does matter to a greater degree is the impact on your teeth. Yes you can remineralise your teeth by eating lots of calcium, but if you’re constantly damaging the enamel by drinking harsh water? I’m not sure of the answer to this problem myself.

Is anyone else having trouble downloading version 6 of the spreadsheet? I can only download version 5.

I couldn’t download it in chrome either but I tried the link in Edge and was able to download.

What a fantastic website and resource… I remember coming across it in my student years a decade ago. It’s sad that each of those mineral water databases have disappeared – a sign of the times I suppose. All good things must come to an end – including the explosion of knowledge that happened in the 2010s? I’m glad I’ve saved your calculator.

This calculator is fantastic! Thank you soo much for putting this together! I’ve been making a 5 gallon keg of Topo Chico every other week and the fam loves having mineral water on tap. I use a $20 brewing scale, sanitize and fill a keg with 5 gallons of distilled water, add the minerals, set the CO2 regulator to 40 psi and a week later have crystal clear mineral water that tastes amazing. It’s incredible. Takes me less than 15 minutes. Thanks again for all this great info it is greatly appreciated. Looking forward to trying some other brands.

Any idea why my san pelligrino tastes like plaster? I did carbonate it, and did wait several days. Also, I made 2 more batches thinking that I did something wrong which is still possible, but it still tastes like plaster.

I had the same problem. What worked for me was to right-click the link and Copy Link Address and then paste that into a new browser tab.