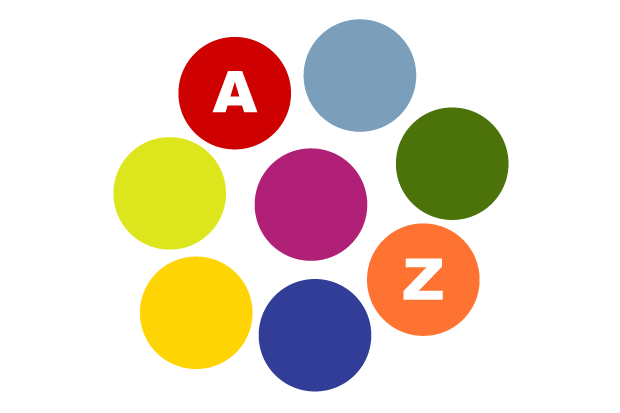

Flavor pairing is a controversial* topic which I’ve blogged about many times in the past. In my last post I suggested that predicted aroma similarity may be a more precise term, and below is an attempt to illustrate predicted aroma similarity (of type 2d according to this classification) by using a color analogy. Let me explain a little first: The letters describe different foods and colors are used to illustrate the sum of the key odorants. The normal situation is that foods A and K (which are perceived as different because they are far apart in the alphabet) also have different colors meaning that they share few or no key odorants. A and B however are close in the alphabet and have similar colors, hence they share key odorants. In some cases foods that we think are very different (A and Z) may turn out to share several key odorants (i.e. have similar colors). The “flavor pairing hypothesis” is a way of finding the “Z” based on predict aroma similarity. I think one reason why we cannot always find the “Z” is that our sense of smell is not very analytical (compared to a gas chromatograph). One thing which I hope becomes clearer with the color analogy is that for a successful pairing one will need contrasting elements as well. This was also a general experience from the TGRWT experiments. I’m very curious whether this communicates well or just makes things even more confusing, so feel free to leave a comment below!

Let us assume that the two foods A and K with no key odorants in common taste marvelous together. Many (or possibly even most?) food pairings are of this kind.

Two similar foods A and C share a number of key odorants. This is no big surprise and most people will say that A and C are quite similar.

Aroma similarity prediction (the “flavor pairing hypothesis”) is a tool to identify Z which (surprisingly) turns out to be quite similar to A because they share key odorants. As mentioned above, finding Z is what is difficult.

Let us imagine a dish where A is a prominent ingredient. It’s combined with classic or empirical pairings (indicated with the different colors – the color tones are chose to match each other).

Based on aroma similarity prediction one can then introduce Z which (surprisingly) is similar to A because of overlapping key odorants.

One can even imagine the case where A is replaced by Z. If the process is repeated a dish can slowly morph into a new dish by exchanging one ingredient at a time.

*Controversial: See for instance the latest issue of Gastronomica where Maurits de Klepper criticizes flavor pairing under the title “Food Pairing Theory – A European Food Fad”. It’s an interesting piece and I recommend that you buy access to read it. But I should quickly add that there are a couple of things that I disagree with. What I’ve previously formulated as a flavor pairing hypothesis is turned into a theory, and I also disagree with the formulation that “the more aromatic compounds two foods have in common, the better they taste together”. In my previous blog post on the topic I have reformulated my viewpoint as follows: For foods with a predicted aroma similarity based on the analysis of it’s volatiles there is a good chance that they can be used together in a dish. It’s also a pity that de Klepper doesn’t cover the topic of key odorants (or odor activity values) properly, but mixes up the different categories (2a, 2b, 2c and 2d) of aroma similarity prediction that I’ve outlined previously. Despite this de Klepper summarizes the experiences from TGRWT very well when he says that flavor pairing “is not a guaranteed recipe for success – balancing flavors is what does the trick”. I couldn’t agree more.

Have you come across this recent piece of research: https://www.technologyreview.com/blog/arxiv/27372/

A rather interesting read and it’s clear that there’s a lot more to learn.

J

Interesting thoughts on foodpairing. As for the link that Jonathan gives, I don´t think that the data pool used is the best for this type of data analysis. A better way to come about this paper would probably have been by collecting recipes from top rated restaurants in each region, and comparing those. But never the less, it emphasizes that foodparing might not always be so straight forward.

[…] And finally Martin Lersch explains food pairing with simple analogies. […]

[…] section of the book explaining smell receptors sheds some light on the developing field of “flavor pairing.” Flavor compounds are all organic compounds varying in length and constituent parts. […]

i tried to tackle some aroma theory here: http://bostonapothecary.com/?p=285

i think that looking at how olfaction converges with the other senses can help predict common harmonies.

but it is important to stress that there is no such thing as dis-harmony (dissonance), there are only further removed harmonies (consonance) that we have yet to absorb.

what culinary needs is a solid theory of acquired tastes.

key to acquired tastes is my theory that somehow a reward for dispelling anxiety through attentional distraction overcomes the reward for nutritional value. what we think of as unharmonic is just more attentional and sometimes that is what we need in times of stress to alleviate anxiety.

cheers! -stephen

i’ve been thinking a lot about flavor pairing lately.

another thing to think about when using alliteration of aroma compounds in flavor pairing is the creation of a super stimuli

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Supernormal_stimulus

i tried to tackle it here:

http://bostonapothecary.com/?p=247

the other day i tasted a barolo chinato from a small producer that was all wrong. his aroma choices didn’t make any sense. none where inherent to barolos.

barolo chinato is supposed to be a super stimulus abstraction of barolo. the old fashioned is a super stimulus abstraction of bourbon. applying dry vermouth to gin creates the super stimulus version of gin alone.

[…] involves five different distinct dimensions of perception. We’ve seen a lot of material on flavor pairing and neurogastronomy lately- this article is as good a place to start as […]