Readers well aquianted with the food blogosphere will likely be familiar with Aki Kamozawa and Alex Talbot’s blog Ideas in food. Since December 2004 they have generously shared pictures, ideas, insights and inspirations online. As chefs they have eagerly integrated modernist techniques and elements in their cooking, allowing technology to improve their cooking whenever possible. No wonder I’ve been a long time follower of their blog! And needless to say I was also exicted to receive a review copy of their recent book Ideas in food: Great recipes and why they work.

First and foremost the book is a great collection of ideas explored by the authors. The ideas are exemplified through recipes (about 100 in total) which showcase the creativity of the authors, from the simple vanilla salt to innovative pasta and risotto techniques, red cabbage kimchi with a built in pH indicator, grilled potato ice cream and practical examples of how hydrocolloids can be utilized. It is certainly an engaging book, and my copy is filled with countless comments, “Try this!”, “Interesting!” and enthusiastic exlamations, but also question marks and disagreement. For some reason the book has been divied into Ideas for everyone and Ideas for professionals, the latter dealing mainly with hydrocolloids. But why the discussion of starch and gelation is reserved for the professionals whereas the recipe for homemade mozarella which calls for lipase, citric acid and rennet is placed in the “for everyone” section, eludes me.

I suggest you have a pencil ready when reading the book!

As the title suggests there are not only ideas and recipes, but also exlanations that sometimes dig deep into food science. The real strength of the book are the cases where a deeper understanding of the underlying science leads to new ideas. Having explored potatoes and hydration of starch, a simple yet brilliant idea which comes out of this is the parcooked rice (65 °C for 30 min) which subsequentially allows for a superfast risotto. As elegant is the hydration of dried pasta by soaking in cold water. Once hydrated, the pasta is drained and kept in a closed container/bag in the fridge. When dropped into boiling water the pasta will cook as fast as fresh pasta. Combining this with other ideas led to a mac’n cheese made from roasted pasta that is smoked and then hydrated in milk, reserving the excess milk with the surface starch for later stage to help thicken the sauce.

Pasta hydrates in cold water (1:4 ratio of pasta to water) within a couple of hours. The fully hydrated pasta cooks within a couple of minutes.

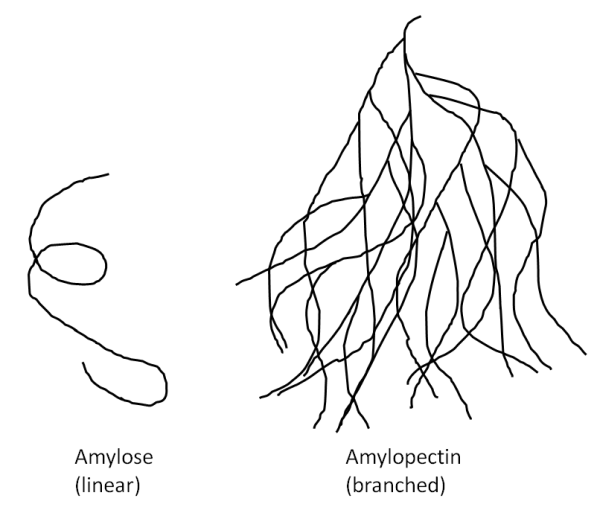

Explaining the science of food and cooking in lay terms is difficult, especially when striving for simple and correct explanations. On some occasions the authors strike a good balance here, but at times the explanations are either too simplistic or too detailed to be of any real help. I was often left with a feeling that the text desperately called for illustrations for the reader to properly grasp the concepts, for instance in their discussion of amylopectin, amylose and starch granules. Perhaps it’s because I’m used to science text books, but the fact that Ideas in food doesn’t have a single figure, diagram or photo is a drawback in my opnion.

Understanding how amylose and amylpection would be easier had they included a simple drawing like this one.

Ever since reading Hervé This’ book Révélations gastronomiques (available in German as Kulinarische Geheimnisse, not available in English) I have appreciated the approach that combines recipes with answers to the many whys that pop up in my mind. Comparing Ideas in food: Great recipes and why they work with This’ book, what shines through at places is the author’s lack of scientific training. Without doubt they know much more food science than the average chef, but it is surprising for instance that the Maillard reaction is not mentioned in their discussion of stocks. And the precision of the recipes is often questionable, especially regarding their use of metric units in the first section. Saying that 1/2 cup of milk equals 130 grams makes sense to me because I expect to see a rounded number. But an online conversion calculator I often use says that for milk 0.5 US cups = 121.8 g = 118.3 ml, so I would naturally have rounded this to 120 grams. On the other hand, when the authors state that 8 3/4 cups of water equals 1968.75 grams the precision implied by the number of digits will make for a good laugh for scientists reading this. And I’m puzzled by how the “cups” used apparantly range from 225 to 260 mL – is there something I’m missing here?. The ultimate solution to this of course would be to eliminate the United States customary units alltogether (sorry all Americans!). Ironically this is exactly what the authors did in the “Ideas for professionals” section.

In the light of the recent paper on the 6X °C egg the whole chapter on “perfect” eggs seems a little outdated. The recipes are probably fine (I haven’t tested them), but I was surprised to read that egg whites coagulate from 60-65.5 °C (this must be a typo) whereas egg yolks coagulate from 65-70 °C (true, but they start to coagulate at a lower temperature, and it’s a function of time and temperature).

To conclude, the compilation of great food ideas is what I found most rewarding in the book. And despite the shortcomings mentioned above I would wholeheartedly recommend the book, simply because of all the nice examples of how a new technique or theoretical insight can be extrapolated into related areas and lead to new ideas in the kitchen. I suggest that you get Ideas in food: Great recipes and why they work for it’s collection of ideas and the creativity of the chefs. But if you’re interested in the whys of cooking you will be better served by other books, the obvious choices being On food and cooking and Keys to good cooking by Harold McGee or The science of cooking by Peter Barham.

Ideas in food – Great recipes and why they work

Aki Kamozawa and Alexander Talbot

320 p, no illustrations/photos

2010, Clarkson Potter

ISBN 978-0-307-71740-5

Martin, thanks for the thoughtful review. I too found it confusing that Alex and Aki’s book completely omitted pictures, whereas their blog consistently teases with tantalizing visuals of food sorely lacking supporting text. But I would argue Alex and Aki’s strength lies in what they leave in the mind of the reader. Their blog makes me wonder “how did they do that?” while the book makes me fantasize about how a recipe might look. After reading the book cover to cover in one sitting (it makes a great kindle download, by the way), I found myself craving more – and isn’t that what great cookbooks should do?

Thanks again, and keep up the great work. Love the blog!

Kevin: Good point there about blog filled with pictures (but hardly any recipes) and a book which is kind of the opposite. Had they combined the two, and maybe even thrown in a scientist on the team one can only imagine what they could have achieved!

Not that I have the answer to the points made here, but I just kind of assumed the book was published in its simple format because of financial reasons… an incredibly accessible book for an incredibly low price.

Sure they could have employed a team of scientists, paid for high detail color formatting, sliced a combi oven in half, but…. oh wait, that book is already out and I can’t afford a copy.

“Great Recipes and Why They Work” however, is extremely affordable and is sitting on my bookshelf right now.

You are not fair chadzilla.

You cannot address together lack of images and lack of solid scientific background by means of financial resources. It sounds like “the book is going to be cheaper if we write it inaccurate”.

So goes for “they could have employed a team of scientists”. Hervé This or Harold McGee have written wonderful books without relying a team of scientists. Not even mentioning blogs like this that are far more accurate than Ideas in Food.

By the way, I think Alex and Aki’s book reflects their blog, the big problem being a certain degree of presumption. Often their posts sound like “we are genius” or “we are sharing a big secret”. And often their ideas are not original at all (is it so difficult to give credit?!?) or the explanations are kinda sloppy.

On the other hand they are really good at just playing in the kitchen with a lot of expensive stuff, both ingredients and tools.

Having an interest in literacy vs. science and science literacy (yes, they’re two slightly different things), I found your review and the reader comments interesting.

Things you write surely will be affected by where you come from. My mathematician colleagues and pedagogics colleagues would put the very same thing differently if they were to describe something (e.g. the mathematicians would use bullet lists where the pedagogy people would write narratively) . In science books, you’ll usually see lots of figures and illustrations, and these carry quite a lot of content which the text does not. I’ve always thought of the Ideas in food blog as a feast for the eye rather than bearing scientific explanations. Perhaps because the authors do not have a scientific background? In fact, research shows that many students/pupils consider the purpose of figures, schemes and illustrations in science books to be decoration rather than to carry subject content.

Your analysis, Martin, I guess is a matter of sociology rather than lack of science (but maybe the latter as well). In that respect, I differ from Chad’s opinion because it’d probably not be very expensive to include illustrations such as Martin’s line drawing of starch above.

Actually, the same phenomenon can be seen when science people approach other fields, such as sociology and pedagogy. One example is the debunking of cooking myths by science people which often tend to lack historic and sociological insight.