Maybe I have a hangup on soft boiled eggs, but I’m deeply fascinated by how something simple as an egg can be transformed into such a wide range of textures. I’m talking about pure eggs – no other ingredients added. Playing around with temperature and time can result in some very interesting yolk textures – yolks that are neither soft nor hard, but somewhere inbetween. Two examples from the blogosphere are Chad Galliano’s 90 min @ 63.8 °C egg yolk sheets and David Barzelay’s 17 min @ 70.0 °C egg yolk cylinders (both bloggers giving credit to Ideas in food and Wylie Dufresne respectively).

In 2009 I wrote about my journey towards the perfect soft boiled eggs. Equipped with a formula I knew what I wanted, but it wasn’t so easy after all. Since then I’ve tried to model experimental data from Douglas Baldwin as well as data from my own measurements of egg yolk tempereatures when cooked sous vide (pictures of how I did this at the end of this blog post). I never got around to blog about the results, and now there’s no need for it anymore: The egg yolk problem has been solved! And the question that remains is: How we can utilize this in the kitchen?

The break through came this year with a paper by César Vega and Ruben Mercadé-Prieto entiteld Culinary Biophysics: on the Nature of the 6X°C Egg [1]. In my opinion it’s a brilliant example of molecular gastronomy: the results are practical enough for chefs and technical enough for scientists. This paper holds the key to unlock the true potential of egg yolk texture, and with it every chef can reproducibly prepare yolks with textures in the whole range between soft and hard. If you think I sound a bit exalted, you’re absolutely right.

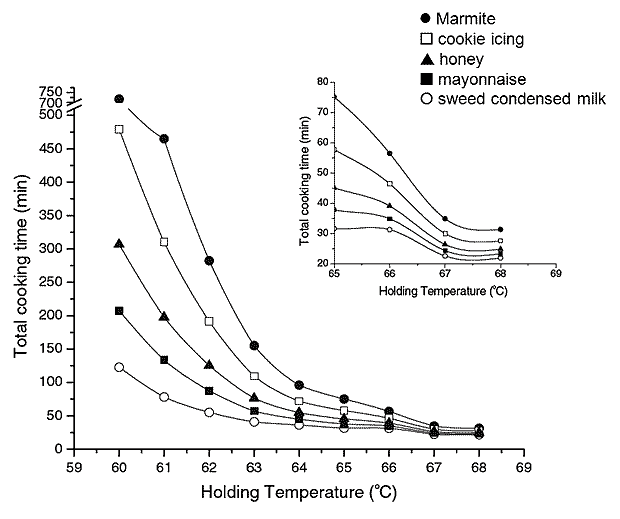

Eggs cooked at low temperature have been all around the internet for the last couple of years, but a general feature of all these posts has been a focus on temperature. This has been the generally accepted truth. Even Hervé This in an interview with Discover magazine claimed that “Cooking eggs is really a question of temperature, not time”. But the present paper counters this. It’s main conclusion is that the texture of the egg yolk is a result of the time-temperature combination used, it’s thermal history if you like. If you’re interested in the details of the paper I suggest you jump directly to the pdf (I could download it for free some days ago, so give it a try), but if you’re only interested in the results, read on! A practical way to measure egg yolk texture is by using a rheometer. It’s a fancy piece of equipment that measures viscosity (and for those of you who are technically inclined – it measures viscosity as a function of shear rate). And what César and Ruben have done is to prepare a graph that shows the viscosity of a large number of temperature and time combinations. It’s a so-called iso-viscosity plot, meaning that once you have decided which viscosity you want the graph will show you all the temperature-time combinations that will give the desired result.

The figure shows how an egg yolk with a texture resembling one of the reference foods can be prepared by chosing any temperature-time combination along the respective plotted lines. (The figure is used with kind permission from Springer Science+Business Media: César Vega and Ruben Mercadé-Prieto in Food Biophysics 2011, 6:152-159, Culinary Biophysics: on the Nature of the 6X °C Egg, figure 8, page 158. The legend overlay has been added by me for clarity.)

For chefs, and even for chemists not working with rheology, it’s difficult to relate to numerical values of viscosity. To get around this the authors did a clever thing by measuring the viscosity of a range of semi-solid foods that may function as reference points: sweetened condensed milk, mayonnaise, honey, cookie icing and Marmite. You can use the iso-viscosity plot shown above to find different time-temperature combinations that give the same yolk viscosity. To use the plot, first decide which texture you want the egg yolk to have. Let’s say you’re in for a honey like texture (filled triangles). Pick a temperature, draw a vertical line until it crosses the line plotted through the triangles and then a horizontal line from there to the time axis. Repeating the exercise for different temperatures will give the different time-temperature combinations that all give a honey like yolk texture; in this case 310 min at 60 °C, 200 min at 61 °C, 125 min at 62 °C, 75 min at 63 °C, 55 min at 64 °C, 45 at 65 °C, 40 min at 66 °C, 26 min at 67 °C and finally 25 min at 68 °C will all do the trick. With a temperature controlled water bath one can chose whatever combination one likes, but if using a large pot of water and manually turning the heat on/off it’s advisable to cook the egg yolk in the lower temperature range. Also, the authors state that it requires a bit of practice to obtain different textures at temperatures above 66 °C.

The paper only deals with egg yolks. At the given time-temperature combinations the white will remain more or less runny. If only the yolk is to be used this doesn’t matter. But if serving the whole egg a simple way to set the egg white is to immerse the egg in boiling water for 2-3 minutes. Alternatively for a little longer at 85 or 90 °C. A comment made by Olly Rouse to my previous post on eggs suggests 8 min at 90 °C followed by cooling at 55 °C is perfect to set the white. However, if the eggs are to be “cooled” at 6X °C maybe 6-7 min is enough. What complicates matters even more is that at 6X °C convection inside the still runny egg white contributes significantly to the heat transfer, but I assume that this is negligible in combination with the longer cooking times in the lower 6X °C range.

Now that all possible egg yolk textures are available the question is: How we can utilize this in the kitchen? Apart from preparing soft boiled eggs, are there any applications in cooking? I’m sure there are many good ideas out there just waiting to be realized. If you blog or twitter about your ideas for utilizing precisely cooked egg yolks I suggest that you tag your blogposts with 6Xyolk and your tweets with #6Xyolk. Then everyone can easily follow up on the progress.

From my own experiments with measuring the core temperature of eggs cooked sous vide: The pictures show how I cut a thin slice from a plastic wine cork, pierced it with a philips screw driver, glued it to an egg, carefully pierced the egg shell with the same screw driver and finally introduced a thermocouple into the core of the egg yolk. There was enough friction between the thermocouple and the wine cork to allow the egg to be suspended by the thermocouple in the water bath. Temperature was logged using myPClab from Novus. Prior to the measurement the egg with the inserted thermocouple were left for several hours in the fridge for temperature equillibration.

[1] Vega, C.; Mercadé-Prieto, R. Food Biophysics 2011, 152-159. DOI: 10.1007/s11483-010-9200-1

I’m so happy to see this finally published! I know Cesar had worked on it for a long time, completing hundreds of experiments- I think once it’s revealed to a wider audience of chefs it will be used to tremendous effect!

This is definitely cool. The part that doesn’t make sense to me is that this seems to ignore the fact that the inside of the yolk takes longer to reach a given temperature than the outside, and hence has a different texture. Perhaps the difference is negligible?

I’d love a graph showing two curves: how long it takes the outside of the yolk (of an intact in-shell egg) to come up to target temp in a bath at target temp, and how long it takes the center of the yolk to come up to temp in a bath at target temp. Sounds like your data might adequately measure at least one of those two variables, for at least a few temps.

Hi.

The white spheres floating in the water bath are insulators?

Michael: Yes – let us hope so. And as mentioned I encourage chefs and to publish and tag their experiments with #6Xyolk on twitter.

Barzelay: Yes – with the long cooking times involved this difference becomes negligible.

Giuseppe: Yes – styrofoam spheres that reduce evaporation from the surface.

Good blog, thanks. I have a sous vide supreme and I’m thinking of experimenting with some eggs, but I did not understand a couple of pieces of the puzzle above. I’m trying to serve the whole egg, not just the yolk.

1) wouldn’t the starting temperature of the egg make a difference in the timing, especially the higher the holding temperature?

2) I did not understand the sequence you mentioned for serving the whole egg. Would you plunge the eggs into the boiling-ish water before or after you have set the yolks, and would there be some sort of cool down period between the setting the yolk and setting the white?

1) As I read the paper, it seems that as long as you stay at 62 °C or lower it doesn’t matter.

2) If you set the white first the egg white will be less efficient transferring heat to the yolk, so this would maybe influence cooking times. But again – if you stay in the lower temperature range it shouldn’t matter too much. Alternatively you can finish it off with a quick dip in a 90 or 100 °C water bath. Since the egg is already at 6X °C it may sufficie with 2 min. But here you really need to buy a box of eggs and do some experiments. And of course – feel free to report back 🙂

1) got it, thanks.

2) it may be that my puny noodle isn’t comprehending this correctly, but it would seem that if you’re setting the white first by going in 90C water for say 3-4 minutes, wouldn’t this get the boundary of the white/yolk well above the intended long soak (say 62C) temperature and start to set at least the outside of the yolk? It would seem that carryover heat would be a problem in trying to get the white set either before or after bringing the yolk to temperature, so you might have to set the yolk, cool down, then shock the white, or alternately shock the white for a brief period, cool down so that the carryover doesn’t hit the yolk too much, then soak for the long haul in 62C water. Am I missing something, are the differences between the yolk and white such that this is not as big a problem as I am imagining?

Thanks, help me get started and I’ll definitely post the results of what I find out. I’m ultimately trying to make a play on a deviled egg but with differing consistencies.

Ryan: You’re absolutely right that it’s not possible to set all of the white without affecting the yolk. That’s why you’ll need to do some experiments to figure out which compromise suits you best. I agree that shocking the white with cold water will allow you to take the white “further” before the yolk begins to set.

The difference between the yolk and white however are to our disadvantage here, because the white is completely set at ~85 °C (although there are probably some time-temperature effects for the white as well…), whereas the egg yolk typically sets in the 6X °C range.

I just now figured out what 6X means. I kept thinking the x was a variable number of degrees, and you were implying something about stepping where the egg had certain properties at 6 times X degrees. It didn’t make any sense to me, so I kind of ignored it. I continued to be puzzled by it. And then finally, I just got that the X is just supposed to be one digit, so it would be in the 60-something degree range. Haha.

Been reading this blog for quite a while now, and I thought I would contribute something… 🙂

After reading the Vegas and Mercadé-Prieto article last night I did a little pilot study this morning, instead of my regular breakfast water-bath eggs. I was also curious about whether to pre- or post-boil the eggs if I wanted to serve the whole egg (with a nice egg white as well).

Egg 1: pre-boiled for 2 min, then water-bath set at 64 degrees C for 64 min (I was trying to use fig. 8 from the article to determine the time needed to get honey-like egg yolk (filled triangle) using 64 degrees C).

Egg 2: water-bath 64 degrees C for 64 min, post-boiled for 2 min.

Starting temp was 5 degrees C for both eggs. No chilling between treatments were performed, and eggs were opened within 30 sec of each other.

Follow link: http://www.dropbox.com/gallery/17135831/2/Sous%20Vide/Eggs?h=c45d2e to see the results.

Btw, is there any way to use an equation to exactly calculate the time needed to get the desired egg yolk texture at a specific temperature, from fig 8 in the article? Using my test as an example, could you calculate the time needed to get honey-like textured egg yolk using 64 degrees C? I know that there are no functions/equations for the curves in fig 8, but perhaps someone can magically bring them forth :).

Way cool! Thanks. I was looking for a way to have the yolk at condensed milk consistency and the white solid. I would then cool it and place the cooled egg in a wide soup bowl along with something else (sous vidded prawns?) and finish with a warmish Riesling bisque.

Cheers,

ChristianS: Thanks for the pictures. Seems there’s still some experimentation to arrive at the perfect egg yolk AND egg white in the same egg… I’m surprised that post boiling for 2 min is enough to set the yolk. So the conclusion so far is that a 64 min/64 °C egg needs >2min pre-boiling or <2 min post-boiling. That's a good start!

Unfortunately my own water bath is having hickups right now - it keeps thinking there's no water left in the water bath although it's full of water. But if I get it sorted out I'll of course join in on the experimentation 🙂

Martin, one of my circulators is missing the little float ball that it uses to determine the water level. So, I simply duct taped the float level indicator into the permanently on position.

The float ball is intact. The circulator now runs for 5-10 min, then a beeping alarm suddenly goes off… I’ve previously had problems with water condensing and shortcircuting (?) the thermocouple. A long period of drying solved this. So I wait and hope and test it every now and then.

[…] This guy has creating the perfect soft-boiled egg yolk down to a science. Make sure to read both Part 1 and Part […]

Your problem to utilize the science of cooking/boiling perfect eggs has been solved commercially for a couple of years as a novelty/gadget called called “PiepEi” (-> ‘BeepEgg’).

It’s a device you store and ‘cook’ along with the eggs, it beeps once the yolk is to your liking (several models with one or more yolk-viscosity levels).

It claims to measure the water temperature and determine the yolk’s temperature by means of solving a differential equation( German: http://www.brainstream.de/techfunk.html, Shop: http://www.amazon.com/DROSSELMEYER-Beep-Egg-Timer/dp/B00265F78C/).

Hence no complicated setup (temperature controllers, baths, thermocouple-equipped eggs). I have not ‘examined’ one yet.

Have you tested dedicated egg-cookers? Thanks for your research.

[…] to Khymos blog post, image from Culinary Biophysics: on the Nature of the 6X°C Egg, fig.8, pg […]

I’m quite familiar with the 6X egg yolk, which I particularly like on asparagus, and in fact I wrote up a blog article with photos that is posted on the Fresh Meals Solutions web site.

But now I want to make a “One Eyed Susan” per the recipe in Rick Taramoto’s “Amuse Bouche”, using quail eggs (because an entire hen’s egg yolk might be too much), brioche and some caviar.

Has anyone worked out the time/temperature to set the white so it can be discarded, and then figured out the time/consistency relationship for quail eggs? If not, I guess I have some experimentation in front of me.

[…] the fast cook technique that Douglas Baldwin developed for Alex (of Ideas in Food) and Martin (of Khymos) I was thrilled. This might be the way to get what I wanted. I was playing around with numerical […]