The authors of Modernist Cuisine: Maxime Bilet, Chris Young and Nathan Myhrvold

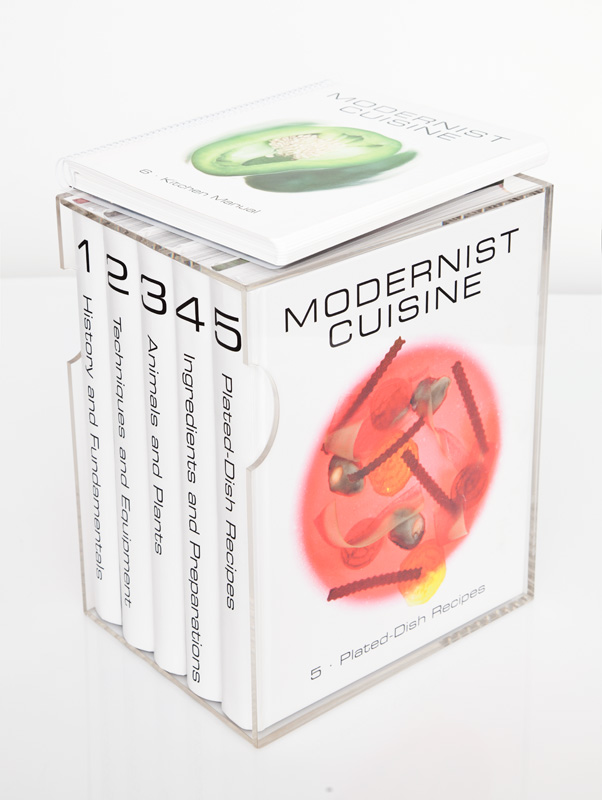

In 2003 Chris Young had an epiphany of a meal at The Fat Duck outside London, and by the end of the meal he knew he had to work with Heston Blumenthal. Things worked out well and after a stage he was hired to build and lead the experimental kitchen at The Fat Duck. In 2007 he returned to Seattle to work with Nathan Myhrvold who at that time was very active on the eGullet forum sharing his research on the sous vide cooking technique. The project that started off as a book on sous vide eventually grew into Modernist Cuisine with 6 volumes spanning more than 2400 pages. After many delays (one being due to a drop test which showed that the casing wasn’t sturdy enough for the books totaling 20 kg) Modernist Cuisine is ready for release in March, and will be presented at The Flemish Primitives event in Oostende, Belgium on March 14. That’s one more reason to visit the event!

Martin Lersch: Congratulations with Modernist Cuisine – it is a truly amazing accomlishment! Will you be present in Oostende?

Chris Young: Thank you. Yes, I’m very excited to be present at The Flemish Primitives to talk about our book, Modernist Cuisine, and to share the work of our team with the broader culinary community. I will have pages that I can sign and that Nathan and Max will have already signed.

ML: You studied mathematics and biochemistry, but how and when did your interest in food arise? And what made you want to combine this and approach food from a scientific perspective?

While at University, I came across an interesting book called On Food and Cooking, and it captivated me. Often, when I should have been studying science books, I was instead busy reading my copy of McGee. It made me realize how much I didn’t know about cooking. So I got to work filling in gaps in my knowledge, cooking my way through cookbooks such as Pépin’s La Technique and La Methode. But it was Thomas Keller’s The French Laundry Cookbook that kept me toiling away into the night perfecting my brunoise, skimming stocks, trussing chickens, braising short ribs, and thinking about becoming a chef.

In the autumn of 2001 I came to the self-realization that spending several more years pursuing a doctoral degree was not in my future. A reasonable question, then, was what should I do? With degrees in biochemistry and mathematics, there was every reason to believe that I was employable. The problem was, however, that I wanted to do something completely different, so I decided to get a job as a cook. Besides, I desperately needed to subsidize my hobby with a job. My grocery bill was getting out of hand! I hesitated only slightly before quitting academic pursuits for a job in a kitchen.

To a lot of my friends, this seemed like a bizarre decision. But for me it was an obvious choice: I had always enjoyed cooking, so I reasoned why not pursue it professionally? I figured that I would become a better cook and make some money at the same time. Well, I was right about the first part anyway. I was lucky to get a job with the talented chef William Belickis at Seattle’s Mistral Restaurant. William took a chance on a me when no one else in town new what to do with a scientist who wanted to become a chef.

But, as I like to tell the story, cooking seems to have been predestined. If my parents are to be believed, my first word was “hot”, uttered after I pulled myself up to the stovetop. As a toddler, my favorite toys were pots and pans. And when I was slightly older, I would attempt recipes from my mother’s encyclopedic set of Time Life’s The Good Cook series of books.

ML: I’ve heard that you had an epiphany of a meal at The Fat Duck outside London, and at the end of the meal you knew that you had to work with Heston. Could you tell me more about that?

The whole story is that at the end of the meal I asked for a stage at The Fat Duck. They said yes, and I returned to England at the beginning of April 2003 and stayed until the end of June 2003. Sometime in April, a newly hired chef failed to return to work, and another chef was scheduled to take a two week vacation. As a result, I ended up working as the garde manger chef. It was a really challenging job, but I loved it. It also gave me a lot of time to interact with Heston during service. He and I just kind of clicked. That June, he asked me if I wanted to move to England permanently and help him open a new kitchen that was focused on developing new ideas and techniques. How do you say no to that kind of offer?!

Getting a work visa turned out to be a bit of a challenge, no one had every tried to get a UK work visa for an experimental chef! So between July of 2003 and June of 2004 I commuted back and forth between Seattle and London. I would do experiments in my kitchen in Seattle and have phone calls with Heston every Sunday morning to discuss the results. Every two or three weeks I would fly to London, land at 7AM, take a taxi straight to the restaurant, and begin work! I would stay for one to two weeks before heading back to Seattle. This has to be some kind of record for commuting to work!

By the summer of 2004 the work permit was sorted out, and I moved to London with my girlfriend (now my wife). Around July of 2004 we opened the experimental kitchen in one of the garden sheds behind the restaurant. About six months later, Heston purchased the Hinds Head pub and I moved the experimental kitchen to a closet in the pub and then later to a house that was purchased with the pub. Located across the street from The Fat Duck, today that house serves as the prep kitchen (downstairs) for The Fat Duck and the experimental kitchen (upstairs). It’s actually a pretty nice kitchen to work in, but when I first moved into the space it was an empty room with broken windows and paint peeling off the walls. You could actually see through the floor into the rooms below!

Over the next 3 years we built up the experimental kitchen and expanded the size of our team as The Fat Duck became successful. For me, it was an amazing opportunity to be part of it from the beginning. I owe Heston a lot for giving me the opportunity to open and run the experimental kitchen, even when he didn’t know how he would pay for it!

ML: In a recent TEDx talk you mentioned that one of the things you learnt from Heston Blumenthal was what a talented cook can accomplish when enabled by science in the kitchen. Is it possible for a chef to really excel today without some scientific backing or a co-operation with a scientist?

Certainly it is possible for chefs to ignore science and still cook great food. Indeed, this is how we’ve cooked for most of history, and we humans have produced some pretty delicious food over the centuries. For me, the reason to be a scientifically-minded cook is for the creative possibilities it brings to the kitchen. Understanding the how’s and why’s of cooking inspires me to be a better chef; it gives me insights into cooking that help me make more delicious and satisfying food.

ML: How did you get in contact with Nathan Myhrvold?

The Fat Duck was where I met my co-author Nathan Myhrvold when he came for dinner. Because he lived in Seattle, and since I was more or less from Seattle too, we stayed in touch. We often exchanged ideas about Modernist barbecue-we’re both very passionate about great bbq-and other Modernist techniques. I would visit him whenever I was in Seattle. In July of 2007, I was thinking about leaving The Fat Duck. My son Jack had been born in April and my wife and I wanted to be a closer to home. I sent Nathan a friendly email telling him that I would be leaving The Fat Duck and that if he wanted to keep in touch he should use a different email address. Three minutes later, I received the following email:

> From: Nathan Myhrvold

> Date: Sat, 21 Jul 2007

> To: chris@thefatduck.co.uk

> Subject: Crazy Idea

>

> Why don’t you come work for me?

>

> Nathan

Later, Nathan told me about the book he had started working on and that I really should move back to Seattle and help him write it. It wasn’t a very hard choice, because even then I knew that this was going to be a once in a lifetime opportunity.

ML: Moving from The Fat Duck to Seattle and working with Modernist Cuisine, what was the biggest change?

One of the biggest challenges for me was writing everyday, rather than cooking. Cooking, with the goal of doing something new everyday, was something that I was comfortable with when I started this book. The writing, however, was a new challenge. Nathan and I really wanted to explain the how’s and why’s of Modernist cooking in a very approachable way; at the same time, we felt that we should not dumb down the relevant scientific concepts. This meant that we had to work very hard at explaining topics as clearly as possible, but in a way that wasn’t boring or irrelevant for a cook. We’ll find out if we succeeded!

ML: A couple of excerpts from the book have been published on the Modernist cuisine website and I must say that I’m stunned by the photographs. At what point during the project was it decided to move on from the ubiquitous black and white to a fully fledged art book?

Modernist Cuisine was never envisioned as being a black and white book. From the beginning, our entire team believed that this should be a no compromise book. We believed that the combination of beautiful photography, great writing, and clearly explained techniques and recipes would make this a unique cookbook that would capture people’s interest.

I will say that back in 2007, when I first started work with Nathan, we thought the book would be a bit smaller-perhaps only 400 pages!

ML: If I may paraphrase Sir Benjamin Thompson (aka Count Rumford), Which discovery in Modernist Cuisine will most powerfully contribute to increase the comforts and enjoyments of mankind?

Actually, I have no idea. This is one of the more intimidating things as an author, I have no idea how people will respond to Modernist Cuisine. I will be as interested as you are to see what ideas and techniques people gravitate towards. But more fascinating than what is in the book now, are the things we will discover need to be put into the next edition? So I suppose that the powerful contribution I hope our book will make is to inspire cooks and chefs to keep innovating and, thus, come up with ideas and techniques that are unknown today.

ML: With more than 2400 pages Modernist Cuisine takes a comprehensive approach to cooking. But in my R&D day time job I often find myself in the position that the more I know about something, the more questions I have. In which areas have you only yet scratched the surface?

Every chapter in our book could have been a lot longer. We tried to make sure we covered the most important points for each of the subjects we covered, but there were a lot of hard choices about what to leave out. At 2400 pages we obviously kept a lot in, but as you say, the more we researched a topic the more there was to know. That’s one of the great things about both science and cooking, there is no end to how far you can explore.

ML: For a student interested in modernist cuisine and molecular gastronomy, what would be good topics to dig into? Where are the white areas on the map?

I really think that we’ve just begun to scratch the surface of what’s really going on in the kitchen. So my advice to anyone would be to dig into the topics that interest you the most. Hopefully we’ll have given you a good idea of where to start looking, but you’ll quickly discover how much room there is to innovate. Very simply, terra incognito in the kitchen is lurking just about everywhere you choose to look.

ML: A majority of the papers published in food science journals deal with food safety, health issues, storage stability, etc. Are the practical questions that arise in cooking or eating not scientific enough for scientists to spend time (and money) on researching them? Or to put it differently – is the pleasure of eating still not a good enough reason for governmental money spending?

I think the unfortunate thing is that traditional scientists generally need funding to undertake their investigations, and, generally, the economic resources haven’t been available to enable them to explore the science behind the pleasures of eating. This was always something that saddened Nicholas Kurti, the renowned physicist who coined the phrase “molecular gastronomy” in an attempt to convince others that the pleasures of the table was a subject worthy of scientific research. Although Nicholas’ efforts certainly inspired chefs such as Heston Blumenthal and food writers like Harold McGee, it hasn’t changed the fact that most gastronomical research done by bonafide scientists has been done on their own time simply because they happen to be passionate about food and cooking.

ML: Sadly there have been no follow ups of the 2004 “International workshop on molecular gastronomy” in Erice. Do you see the need for such a meeting place today where scientists, writers, journalists, chefs and food enthusiasts can meet, eat and discuss in a truly creative and enthusiastic atmosphere? Are there any such meeting places today?

One of my personal regrets is that I was never able to attend one of the Erice conferences. It would be wonderful if someone could create an event that would bring together great chefs and scientists and foster collaboration between these two groups. Sadly, I don’t know of anything quite like this happening today.

ML: How does working at The Fat Duck and with Modernist Cuisine influence your home cooking when you opt for “comfort food”? What kind of dishes would you prepare?

Once upon a time I loved cooking elaborate, time consuming dishes at home. That’s kind of my day job now. So when I have the opportunity to cook for my family or for friends at my home I gravitate towards simple, but delicious things. In the summer I might barbecue ribs on a Sunday, in the winter it might be roasting a chicken or preparing a pot roast of pork. On the other hand, I have been known to do things a little differently in my kitchen than my neighbors-I do keep some liquid nitrogen around, which I use for everything from ice cream to preparing some pretty fantastic smoked ribs.

ML: Harold McGee has recently condensed his cooking experience into “Keys to good cooking”. It gives readers all the practical hints and tips for cooking. To what extent does Modernist Cuisine include practical hints and tips that chefs can use right away in the kitchen?

One of the design features of Modernist Cuisine are margin notes. We used these frequently to include bits of information that didn’t quite fit in the text and also as a way to include lots of practical cooking tips. An example of additional information is this margin note that shows up in one of our plated dish recipes for a beef rib eye:

Rib eye is not one muscle but three: loin (the eye), the deckle (cap), and the relatively unknown, but tender and delicious spinalus dorsi (see page TK). Many cooks know that the deckle is extra juicy and tender. This muscle is actually part of the deep pectoral muscle that is constantly exercised in life by breathing. This makes for a very tender, finely grained muscle (see page TK on why a well-exercised endurance muscle can be more tender). Unfortunately, because it sits on the outside of the roast, it is often overcooked. So it’s best to remove this muscle and cook it separately.

Some of these tips are things that a chef on our team discovered while working on a technique or recipe. For example, in our section on tofus, we have a margin note that explains that an alternative way to quickly make silken tofu is by hydrating 0.2% iota carrageenan and 0.1% kappa carrageenan in soy milk at 85 °C / 185 °F and then chilling it to set.

Some tips help explain how to use part of a recipe or technique in different situations, such as adapting a Russian-style smoked salmon to a Lox-style preparation by slightly modifying the cure.

We used margin notes liberally throughout the book, and we tried to include them with most recipes. In part, this was because we wanted to give people a reason to take the time to read through the recipes, even if they would never attempt a particular recipe because it seems too elaborate.

ML:I have no formal cooking education but I love to cook, and I’m very much looking forward to getting my hands on a copy of Modernist Cuisine. What in Modernist Cuisine do you think will be of greatest interest for the amateurs cooks?

I also started as an amateur cook, with no “formal” training. Modernist Cuisine is the book that I wish had existed when I became passionate and serious about my cooking in the late 1990s. So in that sense, Modernist Cuisine has a tremendous amount to offer any one who is enthusiastic about cooking.

Our book is not just about elaborate recipes prepared with exotic equipment, indeed much of what we cover can be done by anyone in their own kitchen with very little in the way of equipment. To me, the real value of Modernist Cuisine will be its ability to broaden and deepen a reader’s insight into the why’s and how’s behind techniques and recipes. Fundamentally, I believe that by explaining basic scientific principles that govern both traditional and Modernist cooking in a understandable and practical way will be the key to giving cooks greater creativity in the kitchen, regardless of what type of food they are interested in.

The Modernist Cuisine cooking lab in Seattle. Want more? Check out this 26-minute video tour.

ML: If you were to recommend three pieces of equipment/kitchen gear which each cost less than $500 to an amateur cook, what would they be?

First things first, you absolutely should have a good digital thermometer and scale. The thermometer should be accurate to at least 0.5°C (just because a thermometer will display a tenth of a degree doesn’t mean that it is accurate to a tenth of a degree) and the scale should be accurate to at least 0.5g, although 0.1g would be much better (but will obviously cost more). These two tools are as fundamental to me as a knife. Beyond these, I think a pressure cooker is a must. I use them for everything from stocks and sauces, to quickly transforming tough cuts of meat and plant foods into succulent dishes. A pressure cooker is not only a time saver in the kitchen, but can do delicious things that are simply impossible by other means of cooking.

ML: On an art-science axis, where is high-end cooking today? And where do you think it will be in the future?

Actually, this question presumes that art and science are independent of one another, which is something I personally disagree with. To me, science and art are both ways of exploring ideas, and new ideas are the currency of both scientists and artists. The confusion comes because people who have avoided science, or only experienced it in the boring environment of the classroom associate science with facts and structure, whereas they associate art with creativity and whimsy; but actually you need to be very creative as a scientist.

One of the joys I get from my work are applying both the scientist and the chef aspects of my personality. At face value it might seem like these methods of thought are at odds, but really they combine to be the catalyst of doing innovative work in the kitchen. Fundamentally, I believe all chefs are scientists at some level. It’s just a fundamental part of cooking. Anyone preparing a dish is conducting an experiment, which makes them a scientist in my view.

ML: With Modernist Cuisine hitting the shelves next month, is this it, or will there be a sequel?

Well, right now I’m travelling a lot to promote the book, as are Nathan and Max. But certainly there are a lot more areas of cooking that we’re interested in exploring. So, yes, there could be another book. But we’d like to see what people think of this one first.

ML: Chris, thank you very much for fitting this interview into your busy schedule!

Further reading: You can pre-order your copy of Modernist cuisine and while you wait for the books to arrive you can visit their website and blog for more information.

[…] Interview with Chris Young · Martin Lersch interviews Chris Young, one of the authors of Modernist Cuisine. […]

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Naveen Sinha, ideasinfood, Tracey Black, Andrew Hall, Rolf Lippold and others. Rolf Lippold said: RT @ideasinfood: Great interview with Chris Young of Modernist Cuisine http://tinyurl.com/5rq42lf […]

[…] is an interview with Chris Young – one of the authors of Modernist Cuisine. He was a biochemist and mathematician who decided […]