Loquat fruit (known as pipa in Chinese) piled up at Mercat St. Joseph in Barcelona.

Molecular gastronomy was recently chosen as word of the month (not quite sure exactly which month this was). They give the following definition:

the art and practice of cooking food using scientific methods to create new or unusual dishes

This is not the best definition I’ve seen, to be honest. Why should one limit it to new or unusual dishes? When taken to extremes this only results in gimmickery. Strangely enough there are no hits when I search for “molecular gastronomy” at www.askoxford.com, so one might wonder whether they changed their mind? Personally I feel that molecular gastronomy should strive to improve both home cooking and restaurant cooking. That’s also what I tried to convey with my 10-part series with tips for practical molecular gastronomy.

The Webster’s New Millennium dictionary has this definition:

the application or study of scientific principles and practices in cooking and food preparation

This definition includes both the fundamental scientific aspects and the applications of these. But to me it’s too close to “food science”. Where is the enthusiasm? Where is the delicous meal with tempting aromas and textures? As you might know several definitions have been launched over the last couple of years. My favorite definition is still Harold McGee’s (although he does no longer use the definition himself): “Molecular gastronomy is the scientific study of deliciousness”. In my opinion it joins the two worlds which for too long have been separated – the world of science and the world of gastronomy and everything delicious.

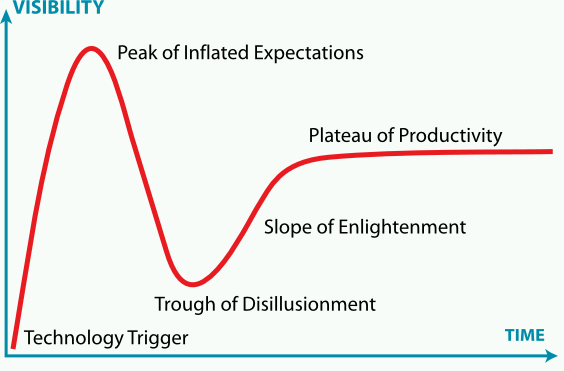

It was a German blog post by Benedikt Köhler over at molekularküche (German blog on molecular gastronomy) that made me aware of the Oxford dictionary definition, and he also reminded me of the hype cycle, a term coined by the US based analyst house Gartner (read more about it in the book “Mastering the hype cycle”). It features the following 5 phases shown below and I agree with Benedikt that these terms can also be applied to the rise and fall (and hopefully also resurrection) of molecular gastronomy:

1. Technology Trigger

2. Peak of Inflated Expectations

3. Trough of Disillusionment

4. Slope of Enlightenment

5. Plateau of Productivity

Phase one started as the term was first used in the 80’s, and I guess it all peaked sometime between 2004 and 2006 with chefs all over wanting to cook with liquid nitrogen and other fancy stuff. Then, with the statement on new cookery by Adria, Blumenthal, Keller and McGee and Heston’s declaration that “molecular gastronomy is dead” we had clearly reached the trough of disillusionment. Today however we’re past that point.

Hype cycle (Concept copyright by Gartner, diagram by Jeremy Kemp under CC-SA).

Benedikt Köhler writes that we’re now on our way to the slope of enlightenment, and personally I think we might’ve reached the fifth phase already, the plateau of productivity. Molecular gastronomy is a term that will live on for years to come, only to disappear as the results and ways of thinking become so common that they’re simply referred to as “cooking” and the result as “really good food” (to quote Michael Ruhlman).

As you might have noticed I’ve decided to stick with one term – molecular gastronomy – for both the scientific, technological and practical parts of “science enabled cooking” (a term Harold McGee uses in The Fat Duck Cookbook – I think that’s a good term). Just like the word “chemistry” is used to describe fundamental research and technological applications I can’t see why the applications of molecular gastronomy (i.e. the food) should be given a different name than the fundamental scientific studies. Some (including Hervé This) have proposed terms such as molecular cuisine or molecular cooking to cover all the practical aspects in order to reserve molecular gastronomy for the “pure science”. There was a debate last year in August on the molecular gastronomy mailing list and Hervé This participated and defended his viewpoint (as he also does in a recent blog post). I actually didn’t take part in the discussion as I had a pretty long private email discussion with Hervé back in 2007 following the EuroFoodChem XIV conference. The conclusion was that we disagree.

I don’t think we should ditch molecular gastronomy, just because it was hyped. But I suggest that we use it to describe more than foams, alginate spheres and liquid nitrogen ice cream. Do you agree?

There are so many new creations and techniques that have been the result of “science enabled cooking”. Due to the widespread dislike of the term “molecular gastronomy” I would also throw into the ring the term “research driven cuisine” as Wylie Dufresne called it back in 2005 for a magazine article. I believe this argument on what to call it will last another few years until we settle on a new description that says it all.

And I’ve adopted the term hyper modern for this very reason (I believe this term has circulated in a variety of sources). I look fondly back at the days when an alginate sphere elicited the awe/joy emotional response that it used to. Now diners ask, “Where is my sphere?” and chef’s groan, “What sphere tonight?” Hyper modern suggests that we are always on the forefront of new technology, new theory and new practice. What is “new” now? Well, let’s be honest, 99% of all molecular gastronomy chefs and cooks are followers not creators. We’ve read books and mimicked web recipes. Sure, many of us like to push our personal comfort zones, but in fact, we’ve pushed nothing that hasn’t been pushed before. And so we are on in the Plateau of Productivity. The modern age of technology has created this. Do we need to hide in a proverbial cave to create something new? I don’t think so. Quite the contrary, I think the answer that returns us to Benedikt’s other stages is when we look at theories and technology not currently used in food preparation and apply them – successfully or not – to modern dining. This to me suggests hyper modern.

I’m not sure we’ve reached the bottom of the trough yet, to be honest. We might be about there. Whilst the cutting edge chefs have repudiated molecular gastronomy as a term (and Heston Blumenthal’s rationale for doing so makes a lot of sense) we’re still seeing the waves of cynicism spreading out. A number of “next year in food” blog posts posited that this year would be the year that “everyone” stopped talking about molecular gastronomy – I think this is going to be the slump year.

I’d expect to see a lot more techniques yet make their way into molecular gastronomy before we reach the steady plateau state. Where’s the ultra-high-pressure cooking? Where’s the flavour compound separation? Where’s the rehabilitation of the microwave? I’ve been doing a bunch of research on cutting-edge food science techniques for Kamikaze Cookery, and there’s a lot more out there.

For me, the only “molecular gastronomy” technique that has really made it into daily use is sous-vide. I make foams a fair amount, spheres only as a gimmick. Liquid nitrogen clearly has lots of practical uses, but it hasn’t really been commoditised. There’s no cheaper Pacojet equivalent (and I’m sure that’ll come eventually). There’s a long way to go.

Totally agree with you there. It is about using principles grounded in science to improve, or validate, what we already know. As far whether we have reached the plateau of productivity, I’m not so sure. As domestic cooks begin to (slowly) adopt the techniques being used in labs and pro-kitchens all over the world (although, of course, not all of these are possible in the domestic setting) then perhaps creativity will take another great leap forward. For me, a person who craves understanding and adores food, MG is the perfect marriage. I might not have access to a full size kitchen lab or even a sous vide bath but I know the importance of seasoning meat before cooking, I know how to make clouds of light mayonnaise (and why it works), I know how Maillard reactions improve the flavours of stews and braises. All these things were born out of MG and are now accepted and adopted within the home. Here’s to more discoveries, and not just foams and alginate baths.

Maybe it’s time to thing of cooking the way we now think of physics, which at one time was simply “natural philosophy.” Then Newton came along, but then, so did Einstein, then Wheeler, and so on. So now we have Classical Physics, Relativistic Physics, Quantum Physics, and so on.

So how about: we had Classic Cooking, which was learning what would kill us and not, Ethnic cooking, which was applying various techniques and ingredients tried around the world, but now available anywhere, and Molecular Gastronomy, which is now a refinement of chemistry and physics to further alter substances for human consumption, in ways that Classic and Ethnic cooking cannot achieve. Like trying to explain M Theory to Isaac Newton.

The question is, are we refusing what the MG means in terms of a new approach to cooking or solely the pure term?. For me, the inclusion of the adjective “molecular” is difficult to accept for people having backgrounds in chemistry, biochemistry or physics. And Hervé This should have recognized the incorrect use of this word from the beginnings of the MG.

From a purely consumer perspective, the problem with molecular gastronomy is that the chefs who practice it are interested in applying the techniques to unique aesthetic exressions rather than to use it to simply improve the way we eat everyday food. If they placed a greater emphasis on consumer satisfaction rather than artistic expression, they would have a lot more commercial success using the technique.

Hugh, I even seem to remember food blogs predicting the “end of molecular gastronomy” one year ago. But just like “Classic cooking” will not end, neither will molecular gastronomy. There just won’t be so much fuzz about it anymore, which is good! And I certainly agree that sous-vide is a perfect example of how molecular gastronomy has reached the average man. The all time most popular post here at Khymos is my post from 2007 on how to prepare a “Perfect steak with DIY sous vide”.

Juan, you make a good point about whether people refuse the word or the approach as such. I guess most people refuse the word, rather than the approach. But that of course depends on what approaches people associate with the term. I think this is where some of the problem lies. I wonder if chefs refuse the term because people tend to associate it with foams and spheres, and nothing else? Even I would refuse the term then if cooking was my profession and I wouldn’t want to be associated with gimmickery.

As a chemist I think “molecular gastronomy” is an OK term as long as we define it. It’s a concept that lives it’s life somewhere inbetween science and cooking, so I don’t think it shouldn’t be interpreted in a strict chemical sense.

Personally I’m most interested in how science can improve my cooking at home. After all this is where I eat most of my meals. The result should either be something that tastes better in a broad sense, or perhaps a more fool proof and robust procedure.

From my point of view, foams and spherifications are part of the “peak of expectation” phase. A new theory is proposed and its most spectacular application are the first to appear, to check its assumptions and to start the work of spread of the message. A bit like some new technologies, they might be at first developed for bellicose purposes but afterwards we might find them applyed in our kitchens….

So I think the we are just getting out of the “Through” caused by the fact that, pushed by the first applications of the theory, we thought that all its new application could be as spectacular.

Understanding that what has been and still is being discovered with this new approach to cooking affects us even in our home kitchen, we are entering the next phase.

I wouldn’t call it a “plateau” but more an asymptotic trend, with a moderate increasing slope. This would correspond to the phase where easy/most evident applications and advances of the theories are almost extinguished and we have just to start working for it as hard as in every other scientific field after their establishment.

The spreading of MG (intended as prof. This defines it) courses in professional environments like universities and schools, will allow the formation of more researchers, more thinking heads that will allow a continuous increase in the knowledges (this will contribute to the hopefully constancy of the progress rate).

As concerning the acception of the words “Molecular Gastronomy”, I guess that a distinction between the theoretical and practical part of it, is due to be; if not merely socially, educationally for sure.

When master in MG will be available (there are already PhD degrees available), we would like to distinguish between a chef and a scientist approach.

Astronomy is not the same thing as Astrophysics, for instance, both deal with the Universe but with different intents. So probably word like “Gastrophysics” or “Gastro Sciences” (“Sciences Gourmandes” seems more appealing though :p) should be formulated.

But it is all just food science really:

http://cdavies.wordpress.com/2009/01/14/molecular-gastronomy-is-part-of-food-science/

Not that I am biased or anything 🙂

Yes, it’s certainly a kind of food science. I’ve even been tempted to use the term “popular food science” some times. But molecular gastronomy is also different from food science. Leafing through food science journals I must say that a regrettably large fraction of the articles are quite uninteresting from a molecular gastronomy viewpoint… Don’t get me wrong here – the science is interesting by itself, but it’s not exactly results I can use in my own kitchen.

On terminology

John: I like the word “enabled”. However, I’d advocate the word “cooking” rather than “cuisine” as cooking makes it sound more general and relevant to the domestic kitchen. Although cuisine according to askOxford does not signify much more than cooking, in my mind the word is more what happens in restaurant kitchens rather than at home.

If MG should not be used for the activity, as Hervé states, my conclusion of good/suitable words that could be included for this activity might be:

– cooking

– science or evidence (or research)

– enabled or based

I also like “evidence based cooking” as stated by Martin Enserink in his 2006 Science article on MG and Hervé This. Maybe is “science enabled cooking” one of the best alternatives?

On the discipline

Hugh: I agree that there’s a long way to go. It’s really surprising that the microwave hasn’t made the leap from thawing and warming fast food. However, things have moved a fair bit already. Good points by Alessio on this. I’d be somewhat surprised if we don’t see any of the results from MG/research reaching a general public soon. Hopefully, some of the less spectacular but more “relevant” or “useful” knowledge might hit the common man soon.

Martin – I am so with you. I am a Chemist, too with a lot of emphasis on organic synthesis and materials science.

Personally, I view cooking as a set of physical and chemical transformations. I view MG as creativity connecting scientific applications to cooking; food science in research conducted in understanding food in it’s various disciplines of biochemistry, chemistry, biology, mat. sci., etc. Neither MG nor food science are plateauing; it is a matter of seeing non-obvious connections and applying those insights.

Look at the average cooks practices: making vinaigrette – that is an emulsion making; monitoring internal temperature of meats – that is a very technical technique; making fudge or caramels – that is changing the sugar crystals into an amorphous phase post Malliard reaction (so many chemistry & mat sci stuff going on here); salting items for browning – that is changing the water content of the surface. My point is that people cooking in their kitchen do utilize chemical and physical methods a lot without realizing it; I think the difference lies in the creativity of the cook. If they are employing more creativity, I view that as MG; where being more technical, just following instructions is utilizing food science.

[…] Martin Lersch asks the question on all our lips – Has Molecular Gastronomy Reached the Plateau of Productivity? Apparently this scientific approach to figuring out what tastes good is rapidly moving up the Slope […]