6. Learn how our senses work

Prolonged exposure to a flavor causes adaption and habituation, meaning that your brain thinks the food smells less even though it’s still present in the same amount. Back in 1953 Lloyd M. Beidler isolated nerves from the tongue of rats to study these phenomena. The nerves were situated in a flow-chamber through which aquous solutions with salty, sweet, acidic and bitter compounds could be flushed. The electric signal produced by the nerve was then recorded and fed to an amplifier and a plotter. Very simplified, the perceived intensity of the stimulus looked something like this (the curve is not to scale in any dimension and it’s my own qualitative interpretation of the data presented in the article):

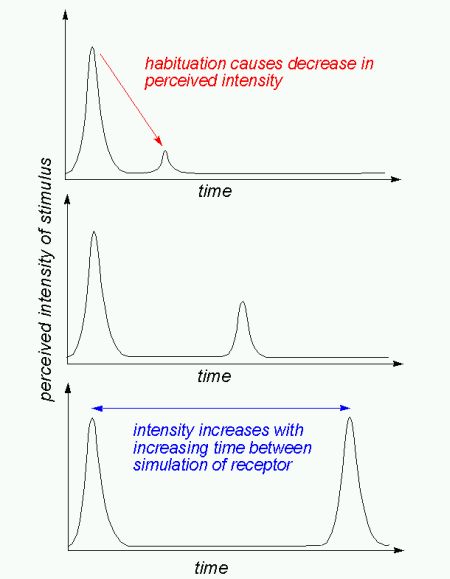

After a short initial latency period a transient is followed by a slower prolonged decrement. There is even some nerve activity after the stimulus has been removed. What is interesting from a molecular gastronomy perspective is that the initial burst of taste quickly fades away – some call it fatigue or adaption. If the same stimulus is applied repeatedly, the maximum intensity of the initial taste burst decreases for each time it is applied. This is known as habituation and is illustrated in the figure below. As the time between stimulation of the receptor increases, the receptor recovers from the habituation and the intensity of the second stimulus increases to match the intensity of the first.

Adaption and habituation are also observed with odor. If you have used eau de cologne or perfume you might have noticed that you can smell it very well once applied, but after some minutes or hours you hardly notice it unless you sniff intentionally for it. The same applies for food.

Variation is the spice of life, and variation helps our senses to overcome adaption and habituation. More technically this has been referred to as “increased sensing by contrast amplification” which I think is a good way putting it. An illustrative example is Heston Blumenthal’s potato purée with small pieces of lime jelly (made with agar agar which is heat stable once it has set). The idea was that to avoid the adaption to the flavour and texture of the potatoe purée, small pieces of lime jelly would help “reset” the taste buds and thereby lead to an increased overall perception of the purée. I’m personally very fond of the variation provided by multiple component dishes. A curry sauce for instance is normally not served alone but alongside many other dishes: rice, dal, chicken/meat/fish, chutney, raita, nan, chapati, pakora, lime juice, salt etc. The different components contrast each other and help bring out the most of the meal.

Contrasts also help us smell better. When we sniff there is an abrupt change in the amount of air passing through our nose. More molecules pass the receptors and the sudden change in their concentration makes it easier to sense them. It has been shown that sniffing in fact gives an optimal odor perception.

Our senses are not unrelated, and there are many interesting articles illustrating this. For instance, adding color to make white wine darker or even red influences the perception of the wine aroma. Along the same lines, consider crystal pepsi which wasn’t a great success after all, probably due to the lack of color. With juice and soups it has been demonstrated that odors smelled through the mouth are perceived differently than those smelled through the nose. Similarily colors can either enhance of suppress the intensity of odors depending on whether they are smelled through the nose or through the mouth.

There are a number of odor-taste interactions. For example, through repeated pairing with sugar, odors become “sweeter”. We become better at detecting sugar solutions if strawberry aroma is added to them, but worse if ham aroma is added. And you shouldn’t be to surprised that both perceived and imagined odors influence taste (that’s right – think of strawberries, and sucrose will taste sweeter!). Heston Blumenthal uses this in the savory ice creams he makes. We associate the cold and rich mouthfeel of ice cream with something sweet, and this influences our perception of the flavour, making it sweeter. In general, the “sweeter” an odor is perceived, the more it enhances tasted sweetness and the more it suppresses sourness. Preliminary experiments suggest that even pure tastants have a smell.

A thing to consider when eating is that our body position influences olfactory sensitivity. And don’t forget that your emotional state also has an effect on the olfactory perception. Emotionally labile people are more sensitive to certain smells and less sensitive to others.

The examples of how our senses are not independant has some practical implications for cooking and eating:

Presentation is paramount, and it is worthwile to consider the art of food presentation. There is a lot to learn from food photography blogs and food blogs with good photos: still life with…, matt bites, 101 cookbooks, la tartine gourmande too mention but a few. Also check out the pictures submitted to the monthly food photography blogging event does my blog look good in this (google DMBLGiT to find out which blog hosts this month’s event).

Taste, smell, texture, mouth feel, temperature and appearance will all contribute to the overall experience when eating and drinking. But also the room, the atmosphere and the people present have an influence. I have previously mentioned the five aspects meal model which has been developed for restaurant settings and takes all of this into account.

Many of the ideas found in this blog post can be expressed in appetizers. With small, well prepared amuses bouche there is variation with every bite, creating excitement and anticipation.

And remember that average food eaten in the company of good friends while you’re sitting on a terrace with the sun setting in the ocean will taste superior to excellent food served on plastic plates and eaten alone in a room with mess all over the place.

Update: I submitted the picture of the cherries in the heading to the monthly “Does my blog look good in this” (or DMBLGIT for short) photo competition for food blogs – and guess what – the picture was the winner of the August 2007 round. This is a great honour, because there are so many good photographers out there with food blogs. Click to view the complete gallery of the August 2007 round.

*

Check out my previous blogpost for an overview of the 10 tips for practical molecular gastronomy series. The collection of books (favorite, molecular gastronomy, aroma/taste, reference/technique, food chemistry, presentation/photography) and links (webresources, people/chefs/blogs, institutions, articles, audio/video) at khymos.org might also be of interest.

The reference to adaptation to the odor of perfume is only valid for “˜ck one‘, but not for “šnormal’ perfumes as Luca Turin (this is more informative) stated in his column on perfume in the NZZ-folio magazine. “˜Normal perfumes’ have different phases of odor release as a direct consequence of the volatility of the components used in the formulation: some fragrances for early release, some for the “˜body of odor’.

Furthermore the there seems to be a fundamental difference between taste and olfaction adaptation: The former adaptation seems to be a function of the chorda tympani nerve (Zottermann, p.114) and is already occurring at sub-threshold stimuli (Pfaffmann, p.90) whereas the later (olfaction) seems to be mediated by a central mechanism (Engen, p.219).

Engen, Trygg in Handbook of Sensory Physiology, Chemical Senses 1 Olfaction, Ed. Beidler, Lloyd M., Springer-Verlag 1971

Pfaffmann, Carl et al. in Handbook of Sensory Physiology, Chemical Senses 2 Taste, Ed. Beidler, Lloyd M., Springer-Verlag 1971

Zotterman, Yngve in Handbook of Sensory Physiology, Chemical Senses 2 Taste, Ed. Beidler, Lloyd M., Springer-Verlag 1971

Interesting comment! I must admit that the the difference between the adaption mechanisms goes way beyond my level of understanding 😉

I am aware that perfumes (and probably eau de colognes?) are designed for a sequential release of odors (but I didn’t know that this is not the case for ‘ck one’ – fascinating!). Regarding eau de cologne, I noticed that the first few days using a new brand I could smell it throughout the day. However, after weeks and months it seems as if I’ve gotten used to it and I’m not able to detect is as well as before. That’s why I’ve speculated about a day-to-day habituation.

I love your blog, and it’s not because I agree with everything you say, but you have lots of clear, well-defended ideas, good links, and the occasional pretty picture. 😉

As far as the adaptation bit goes, in the book “Stumbling on Happiness,” Daniel Gilbert addresses this subject from a neuropsychology perspective using fine dining as the framework. The language of the book is simple, with lots of references and does a good job relating biochemical receptors directly back to the level of happiness experienced.

I don’t know if this does or does not interest you, but the book has actually been quite helpful in my approach to cooking (which, the way I see it should be a way of making people happy) and has relevance to molecular gastronomy in general and this subject in particular.