1. Use good and fresh raw materials of the best quality available.

No amount of cooking and preparation – be it traditional, modern or molecular – can fully disguise ingredients of poor quality. No one will probably disagree with this and it’s elementary knowledge for every cook, yet I include it because after all molecular gastronomy is also about the raw materials you use. Do not always reach for the cheapest products. Eat better, but less – it won’t cost you more, because you’ll just get less calories for the same price!

I will also encourage you to support local producers. This will probably make me sound like a slow food practitioner which is fine, because molecular gastronomy is not in any opposition to slow food or traditional cooking, it’s more about understanding the chemical and physical principles underlying all handling and preparation of food. Part of my motivation when writing about molecular gastronomy is actually to bring it a little more down to earth.

When talking about freshness it’s important to consider how food deteriorates. Assuming that safety and toxicological issues are taken care of, from a molecular gastronomy viewpoint it is interesting to discuss flavor. The most important pathways to flavor deterioration include exposure to air (particularly oxygen), light, moisture, high temperature, bacteria and fungi.

The flavor of foods stems largely from the presence of volatile organic compounds. Because of the low boiling point, these compounds easily escape from the food. And at higher temperatures evaporation of aroma compounds is even faster. Also, many of the compounds can react with oxygen in air. A typical example is the oxidation of fats which gives a rancid flavor. Generally, fats and oils should be stored in the refridgerator to slow down this oxidation, but it turns out there’s an exception for olive oil.

To retain as much of the volatile compounds as possible it is advisable to store spices in tight containers kept in a dark and cool place. If you for some reason need to store spices for a long time, put them in the freezer. Since the loss of aroma comounds is proportional to the surface area of the spice, it’s also a good idea to buy whole spices and grind them yourself immediatly prior to use. I would also recommend the use of spice pastes (such as curry pastes for instance) since the oil helps extract aroma compounds. Such pastes should preferably be stored in the fridge.

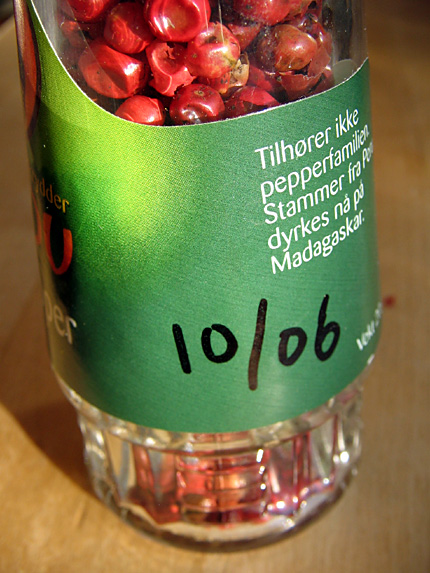

Like me, you probably have many different spices in your pantry. Some of them have probably been sitting around there for years which is far from optimal. Therefore, as a reminder to myself, I have started to mark each spice with the date of opening (or purchase) using a water proof pen.

With fresh fruit and vegetables, finding the right storage conditions can sometimes be difficult, but this pdf from UC Davis provides a quick overview of recommended storage conditions (ie. what should be stored in the fridge and what should be stored on the countertop).

One last example of the importance of correct storage conditions is the staling of bread. Contrary to popular belief, staling of bread is not caused by evaporation of water from the crumb. This is easily demonstrated when you heat a slice of bread in a toaster or a microwave oven. What happens upon storage is that starch and water crystallize. As a consequence the crumb loses its elasticity and goes stale. The aging process proceeds fastest at 14 °C. Because of this, bread should be stored at room temperature – never in a fridge. When freezing bread, rapid cooling is important because the staling is halted below -5 °C.

*

Check out my previous blogpost for an overview of the tips for practical molecular gastronomy. The collection of books (favorite, molecular gastronomy, aroma/taste, reference/technique, food chemistry) and links (webresources, people/chefs/blogs, institutions, articles, audio/video) at khymos.org might also be of interest.

Thanks for putting this as Numero Uno on the Molecular Gastronomy Top 10. It is an affirmation to those who should forget that culinology embraces the same principles as traditional cooking. It is cuisine evolution, not revolution. For myself, I have felt more compelled to use these modern techniques to push the flavor (or natural glutamate levels) of ingredients while retaining texture and moisture… and in some cases achieving better textures. Diners who taste this only know that it’s delicious. They do not usually understand or care to know why. That is the role of the chef. We have been making tremendous new efforts to find and procure great ingredients, and the results are beyond satisfying. It is so much better to talk to the grower than to someone behind a desk.

“What happens upon storage is that starch and water crystallize.” What do you mean? Obviously the water does not crystallize (i.e. form ice).

as an eater, i have to agree w/ this post 100%.

a meal at Keyah Grande (Alex & Aki of Ideas In Food fame) was superb – they are talented & creative chefs but their ingredients were also pristine:

http://chuckeats.com/blog3/2007/01/19/keyah-grande-pagosa-springs-co-rip/

meals @ WD-50 (NY) have been inconsistent. some people complain the food is too weird but, after having 6-7 meals over the past 3 years, i think it’s the inconsistency of the ingredients (and possibly their handling.) hit it on a good night and it sings.

a meal at El Bulli did not achieve a top tier status b/c they served us disgusting tomatoes and various other small slip-ups. in the context of what they were doing, they probably though the ingredient played a tertiary role to the genius of the dish; however, it’s the first thing we noticed as eaters.

[…] 1. Use good and fresh raw materials of the best quality available. […]